With the Armistice to end the Great War, there came the question: what now? The entire population of the British Empire had contributed to “total war”1. Massed armies, mass equipment and mass casualties created unique challenges. In the past, most enlisted soldiers had been buried in common graves far from their families. Only officers had been given special commemorations and sometimes their bodies were even repatriated. The governments of the time felt, however, that the general population would not tolerate that kind of treatment in this modern conflict. These soldiers had committed themselves fully to the cause of their country and they needed to be acknowledged.

During the war, men who did not make it back to the Field Hospitals were often hastily buried by their comrades near where they fell. The National Committee for the Care of Soldiers’ Graves, a predecessor of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, lobbied to locate as many of the deceased as possible and concentrate them into specially created graveyards. Men whose bodies could not be located were to be commemorated on memorials like Vimy Ridge and the Menin Gate.

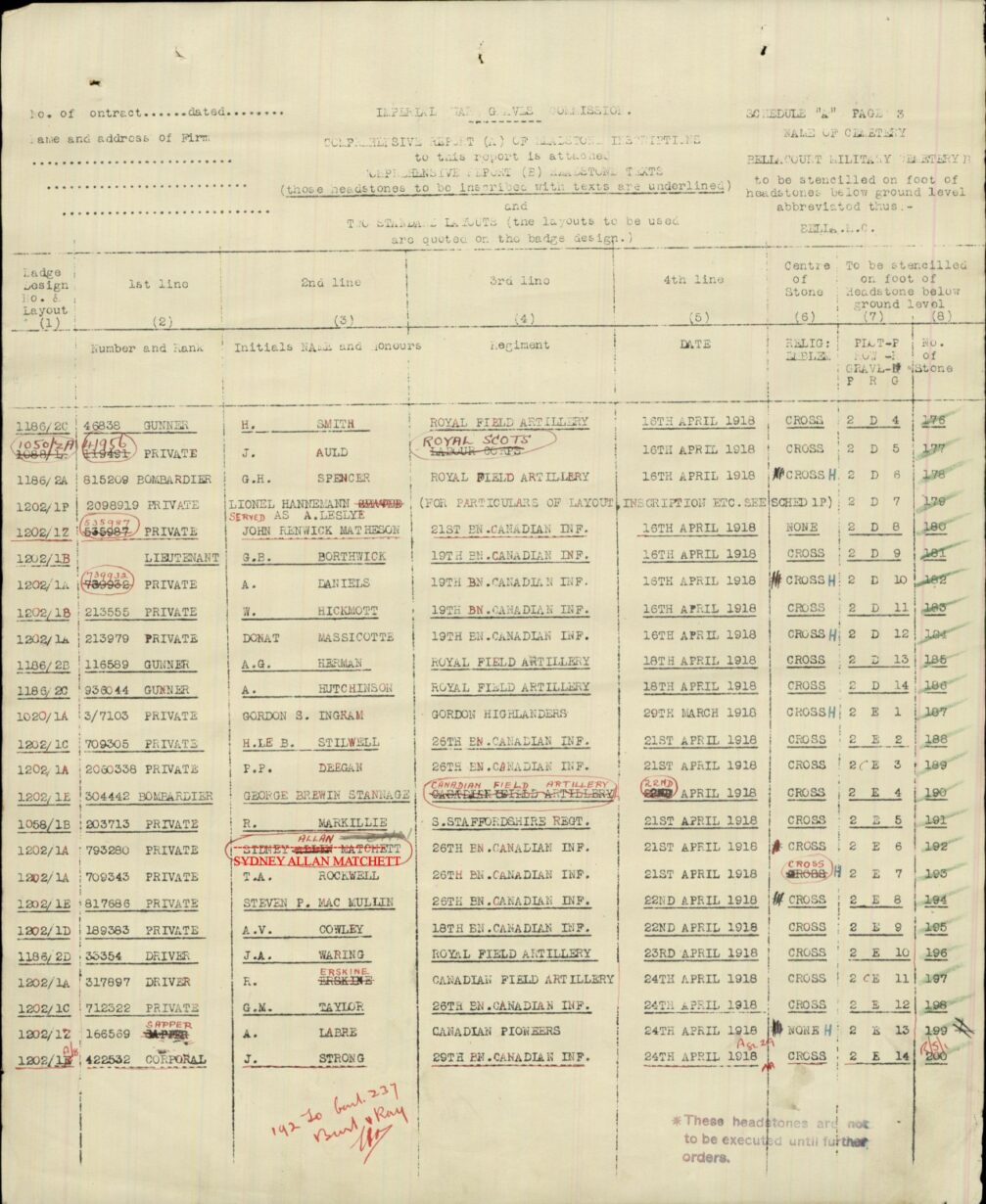

Each casualty was to be commemorated with a standardized tombstone. They would all be made out of white marble. Each would bear a crest either representing the person’s unit or country. In Canada’s case the headstone code was 1202, the maple leaf. Line one would list the deceased’s service number and rank. The second line contained their name and any honours they had been awarded. Third came their regiment. Next came an optional Christian Cross or Star of David. If no religious symbol was added, this space was left blank.

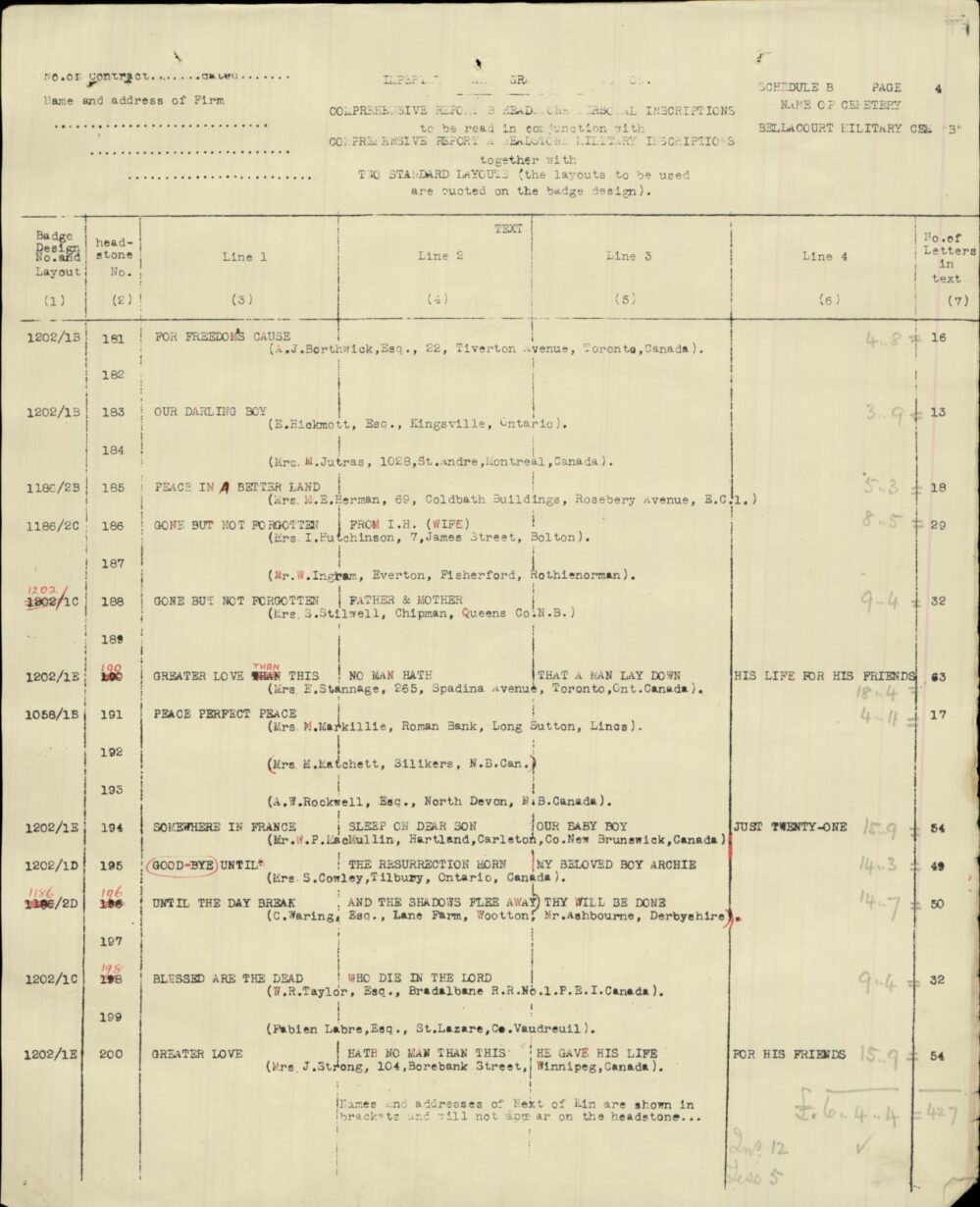

To this point, all that is on the stone was government regulated. However, for the modern viewer, the most interesting part of these memorials are the bottom four lines of text. For the cost of three pence per letter, the family of the service member who had been killed could write a few lines. Even in death, wealth still had its privileges! These epitaphs present a unique insight to the experiences of the common people.

A surprising number of these lines are repeated.

- “Gone but not forgotten, Father and Mother”

- “Great love than this no man hath that a man lay down his life for his friends”

- “Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord.”

Families appeared to be at a loss on how to appropriately commemorate the fallen and selected known phrases or religious statements. Not knowing quite what they should do or what was appropriate, they fell back on quoting the Bible, or Rudyard Kipling, one of the most popular authors at that time.

Not all families were as conventional. Some lines were much more personal and haunting. The families whose words allow us insight into their mourning, pain, or even anger:

- “He made the great sacrifice, my only son”

- “He tried to do his duty”

- “Love and kisses from mother”

- “To my dear son, one of three who gave their lives for the country”

- “The shell that stilled his true brave heart broke mine. Mother”

- “Who died for his King and country at the tender age of 17”

- “Woe to the world should he die in vain.”

What is equally interesting are the number of stones with no contributions. This absence was much more common in the Great War than in the Second World War. It raises all kinds of questions: Did they have no family? Was their family too distraught to write? Were they too poor to afford an epitaph? Or, as was probable in many cases, were they illiterate and could not lend voice to their grief?

World War One was unique in many ways. It was the first truly total war, where all of the resources of the state were focused on executing the conflict. The Commonwealth Grave Commission’s work continues, and their stones bear silent witness to those brave men and women who made the ultimate sacrifice for Canada and the Commonwealth.

Guest written by Kris Tozer for Honouring Bravery

- Total War is when all of the resources of a state – human, natural and capital – are fully directed to the war effort. ↩︎

Sources for further exploration:

Simmons, Louise. “Language of Loss: Canadian English Epitaphs in the First World War.” Strathy Language Unit, February 18, 2020, https://www.queensu.ca/strathy/language-loss-canadian-english-epitaphs-first-world-war. Accessed 15 05 2025.

Wearne, Sarah. Epitaphs of the Great War: The Last 100 Days. Unicorn Publishing Group, 2018.