After the American Revolution ended in 1784 and the first measures to limit slavery were enacted in Canada in 1793, the Black population in Canada gradually increased. While many slaves still served wealthy British citizens and Canadians, many thousands of freed people and emancipated slaves also owned land and property. African Canadians made up a growing group throughout the territory, with large communities in Newfoundland and Ontario.

Many African Canadian men who settled in Canada were Loyalist veterans of the American Revolutionary War. Others were also escaped slaves from the American colonies who made their way to Canada to find freedom. When the United States declared war on Britain on June 1, 1812, many African Canadians were ready to defend their property and communities.

Enlistment

At the start of the conflict, Richard Pierpoint, a Loyalist veteran and former slave, petitioned the British government to create a Black unit to fight the Americans. The petition was rejected for reasons we can only surmise. However, the decision was quickly reversed when the Americans occupied the village of Sandwich (now Windsor, Ontario) in July 1812. The unit was created soon thereafter but headed by a White officer named Robert Runchey, a man with a less-than-stellar military reputation. It is highly possible that he was appointed to the unit as a punishment, to the obvious detriment of its volunteers. For example, during his command, a number of Black officers were assigned to work as servants for White officers! This behaviour obviously did not help recruitment, and by October 1812, only 40 people had enlisted in the unit.

Fighting the Americans posed greater risks to African Canadians, as being captured would certainly lead to their deportation and enslavement. For the American troops, capturing a Black person (regardless of their status) would have been the same as pillaging any other property. Captured Black soldiers did not have the same rights as other prisoners of war and were instead considered as objects.

Historians David Meyler and Peter Meyler identified three Black soldiers who were reported missing on May 27, 1813 after the Battle of Fort George: Anthony Hutts (sometimes listed as “Hults” or “Hull”), Abraham Sloane and William Spencer. The first was captured by the Americans and, as per official reports, died afterwards. While this is very possible, no evidence supports this theory other than the discovery of an unidentified Black corpse on the battlefield. The British authorities listed the other two men as deserters after the battle. However, as the two historians speculate, many soldiers were branded as “deserters” if they didn’t show up for a head count. It is very possible that these two men were killed during the battle and that their bodies were never found. Another real possibility is that all three were captured and resold into slavery somewhere in the United States. While we can’t confirm the fate of these three soldiers, these cases show the potent risk of African Canadians in joining the army at the start of the conflict.

Dedicated service

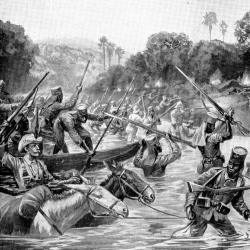

The unit first saw action on October 13, 1812 during the Battle of Queenston Heights. According to official reports, the soldiers fired a first volley before charging against the American troops, who immediately surrendered. After the battle, the unit was sent to Fort George so that it could reorganize and keep training over the winter. This was when it received its official name of the Coloured Corps. As mentioned above, the Coloured Corps’ second exploit was at Fort George on May 27, 1813, when American troops landed nearby and forced the defenders to retreat. As historian Gareth Newfield writes, the Corps’ activities are difficult to establish from that point. However, it is very likely that the unit stayed active and took part in operations and skirmishes against American troops in the following months.

The British forces retook Fort George in December 1813 and found it in a pitiful state. The British needed men to rebuild the fort, and the Coloured Corps had lost a large number of soldiers in the previous months. It was decided that the unit’s remaining soldiers would be put to work as carpenters. Was this decision racially motivated? Most likely, as Gareth Newfield rightly points out. After all, up until the First World War, the British Army would generally reserve construction work for its Black soldiers. Unfortunately, these suspicions can’t be confirmed, as the officer who approved the soldiers’ transfer was killed a few days later.

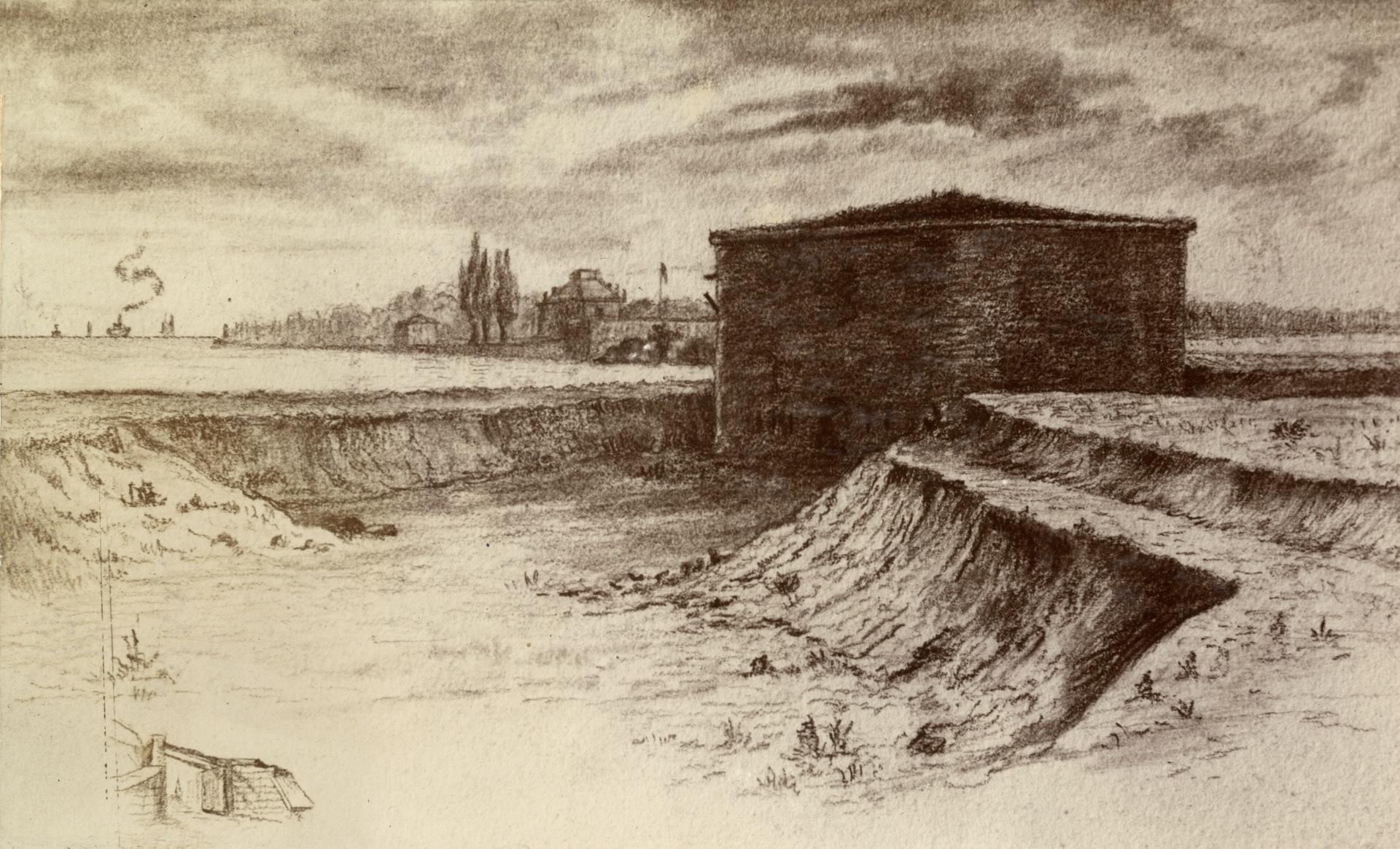

Despite being assigned new duties, the Coloured Corps soldiers of course worked very hard. After Fort George was repaired in the spring of 1814, the unit was tasked with building a new fort in Mississauga, which was considered a priority to prevent American troops from advancing along the adjacent river. Until the end of the war, the Coloured Corps continued building the fort and on one occasion even had to defend it against the Americans.

A great contribution

As historian Amadou Ba points out, Prime Minister Stephen Harper was quick to cite the War of 1812 as one of Canada’s founding events. Going by this same logic, the soldiers of the Coloured Corps therefore also helped found the country. Leaving aside debates over historical writings on the War of 1812 and its influence on Canadian identity (a subject best left to greater experts on this topic!), we can at least agree that African Canadians made an undeniable contribution during this conflict.

They risked a great deal by taking up arms against the Americans. Unlike other soldiers, these men had to fight resolutely to preserve the freedoms and rights they had won over the years. From freed men to escaped slaves, all soldiers of the Coloured Corps put every effort into preserving their identities and fighting for a cause they cared about.

Cover photo: A plan of the Mississauga fort drawn by a certain John Smyth in the early 19th century (source: Public Archives Canada).

Article originally written by Julien Lehoux for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Amy Butcher (traductionsamyb.ca).

Sources:

- « The Coloured Corps: Black Canadians and the War of 1812 », L’encyclopédie canadienne/The Canadian encyclopedia.

For a more academic approach:

- Amadou Ba, L’histoire oubliée de la contribution des esclaves et soldats noirs à l’édification du Canada (1604-1945), Éditions Afrikana, Montréal, 2019, 300 p. (in french).

- David Meyler et Peter Meyler, A Stolen Life: Searching for Richard Pierpoint, Toronto, Natural Heritage Books, 1999, 141 p.

- Gareth Newfield, « Upper Canada’s Black Defenders? Re-evaluating the War of 1812 Coloured CorpsColoured Corps », Canadian Military History, vol. 18, no. 3, 2009, pp. 31-40.