During the First World War, thousands of Canadians went to their local recruitment office to enlist. However, not everyone was eligible to join. The Canadian Expeditionary Force had specific requirements on what made a soldier fit for service. One requirement that stopped many individuals was age. Generally, a person had to be between the ages of 18-45 to enlist. In some cases, underage Canadians also could enlist if they had parental permission. However, historical documents demonstrate that many recruits successfully lied about their age so that they could serve in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. In this blog post, we will explore some of the most extreme examples of this phenomenon.

William Henry Hutchinson

Age according to attestation paper: 12

Actual age at enlistment: 11

William Henry Hutchinson’s story of enlistment is very unusual, even for an underage soldier. He was born in 1905 in Kent, England. In 1908, his family moved to Montana, where his father unfortunately died in a workplace acident. Shortly after, the family moved to Vancouver, British columbia and his mother remarried. As a child, Hutchinson took a part-time job selling the local newspaper, The Province. With his earnings he purchased a bugle. One day while he was playing in the backyard, some soldiers from the nearby military camp heard him practicing and asked him to join their band as a bugle boy. According to militia regulations at the time, “boys of ‘good character’ between the ages of 13 and 18 could be enlisted as bandsmen, drummers, or buglers”. He enlisted in June 1916 with the 211th Battalion. Interestingly, Hutchinson incorrectly gave his year of birth as 1904. This was likely to make it appear that he was closer to the required age than he actually was. Since he only was 4’ 5’’ tall, well under the height requirement in 1916, Hutchinson needed a special uniform.

As a young child, Hutchinson would never have been allowed to join the battalion in Europe. He was therefore discharged on December 2, 1916, a few weeks before the battalion was to go overseas. While that should have been the end of his war service, he snuck aboard the HMT Olympic, with the help of some of his friends in the battalion, when they set sail on December 20th . Overseas he became the battalion’s ‘mascot’ and presumably, his friends helped him lie about his age to others who did not know him. In March 1917, the battalion was transferred to the Canadian Railway Troops. By April April Hutchinson found himself in France on the front. While there, he worked as a dispatch messinger for troops operating field telegraphs.

Since he was a stowaway, there are very few records of Hutchinson’s time in France. According to an interview given later in his life, Hutchinson was wounded in the right leg in 1917 somewhere near Neuve-Église, France. It was only after he went to the hospital for treatment that the authorites discovered his age and sent him home. Although there are no records of this injury, Hutchinson’s discharge papers do support that some sort of injury occurred, as it is noted that he received one gold casualty stripe. However, his military records also suggest that Hutchinson was sent home after his mother found out that he was in France and formally complained to the military authorities. Regardless of how it happened, Hutchinson was sent back to England in September 1917 and arrived back in Canada on November 30, 1917. Due to the peculiar nature of his service, he did not receive payment for his service overseas until after he returned to Canada. In fact, it was only after the signing of a special Order in Council on January 12, 1918 that the government recognized his service.

In 1919 Hutchinson reenlisted, this time with the 11th Battalion of the Canadian Garrison regiment, and stayed with the regiment until demobilization. After the war, he briefly worked as a professional boxer, calling himself Billy ‘Kid’ Nash (Nash was his step-father’s surname). By the 1930s he was working as a longshoreman. Hutchinson passed away at Shaughnessy Hospital in Vancouver in 1969 and is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park. He was the youngest known soldier to serve overseas with the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

John William Boucher

Age according to enlistment papers: 49

Actual age at enlistment: 721

John William Boucher was born in Port Maitland, Ontario in 1844. His father died when he was young and his family sent him to a boarding school. During the American Civil War, he enlisted with the 24th Michigan Infantry and later with the quartermasters department in Nashville. After the war, he worked for multiple railway companies and eventually settled in Gananoque, Ontario. There, he got married and raised a family.

When The First World War broke out in 1914, Boucher was a widower and far past the age for military service. He tried enlisting several times but was always rejected. In 1917, the government adjusted the maximum age for enlistment into railway battalions from 45 to 48. Seizing the opportunity, Boucher tried again to enlist. During his medical exam, he lied to the doctor and said he was 48. However, he must have miscalculated when filling out his attestation paper because he gave his birth year as 1867. This would make him 49. In either case, the recruitment officer, who knew Boucher was lying, miraculously green-lit him.

Boucher arrived in England with the 257th Canadian Railway Battalion on February 27, 1917. Because of his age, his fellow soldiers gave him the nickname “Dad”. By May 1917, he was serving in France. For months Boucher kept up with men half his age while building the railway systems needed to move supplies to the front. Eventually, however, his age caught up with him and he began suffering bouts of arthritis. After being forced to share his actual age with a medical officer, he was taken off his posting on November 21, 1917.

After returning from the war, he moved to Syracuse, New York. While living there, he wrote about his experiences in the war and published the story in installments in the Post-Standard newspaper. He also became active with the local legion and spoke publicly on his time in the war at public events. Later, he moved to Miami with his daughter. He died in 1939 at the age of 94. According to our research, he is the oldest known soldier to serve in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in continental Europe.

William John Clements

Age on attestation paper: 44

Actual age at enlistment: 78

William John Clements was born on April 12, 1837, on the island of St. Helena to British parents. When he was young, he enlisted with the Royal Artillery in England. He immigrated to Canada when he was in his 30s and worked as a carpenter to support his family. In 1874 he enlisted with the 30th Wellington Rifles and rose to the rank of Company Sergeant Major. After serving 38 years in the militia, he left the Wellington Rifles in 1912.

The First World War began two years after Clements retired from the militia, but he still wanted to take part. He was able to officially enlist with the 34th Battalion on March 17, 1915, just a few weeks shy of his 78th birthday. He put his age as being 44. Interestingly, by this point, at least two of his adult children were in their 50s. Likely, as was the case with John William Boucher, everyone knew he was not actually 44, but somehow the recruitment officer allowed him to join anyway.

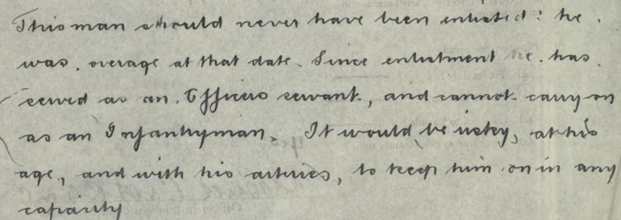

Clements arrived in England on October 31, 1915. During his time in England, he worked as an officer’s servant. However, it became clear that he was in no way fit to serve. Not only was Clements deaf due to his age, but he also had arteriosclerosis. He was sent home and discharged in Quebec on August 7, 1916. In 1933, Clements died at the age of 96. Although he had a long military career, his tombstone at Greenlawn Cemetery in Guelph, Ontario pays homage to his short time serving in the First World War. Although he never saw action on the battlefield, Clements is the oldest known soldier to serve in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

So, is age just a number?

In the minds of William Hutchinson, John Boucher and William Clements, the desire to serve in the Canadian Expeditionary Force outweighed the consequences of lying about their age. Ultimately, their age eventually caught up with all of them and they were forced to return to Canada. Although these examples show the extreme lengths that people took to lie about their age, they are by no means the only examples. Although we will never have a definitive number, researchers estimate that around 20,000 underage individuals served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. This does not include the many other overage individuals that also served.

Written by Anthony Badame for Honouring Bravery

Sources:

Clarke, Nic (2015). Unwanted Warriors: Rejected Volunteers of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. UBC Press: Vancouver.

Personnel Record for John William Boucher

Personnel Record for William Clements

Personnel Record for William Hutchinson

The Oldest Legionnaire (1938, February). The American Legion Magazine.

Youngest Veteran Found (1939, October 7). The Vancouver Daily Province.

Footnotes

- Since his birthday was in December, William Boucher would have only just turned 72 when he enlisted in 1917. However, as he was in his 73rd year, he is often noted as being 73 when he enlisted. ↩︎