Beyond liberation

The Allies arrive

As documented by their war diary, when Le Régiment de la Chaudière came to the village of Bernières-sur-Mer on June 6, 1944, “The French were quite welcoming, and many cheered us on from the ruins of their homes.”

The French saw the arrival of the Canadians as the first step in their liberation and, beyond that, the end of the war. Wherever they went, the Canadian soldiers were hailed as heroes, and civilians would go up to them to celebrate the victory.

“And I remember going through the country side. It was very exciting because every village we would go past the people would come out and with flowers in their hands and when we stopped they would bring wine and pastries and fruit for us to eat.”

—Frank Wong, mechanic, Veterans Affairs Canada

Yet not everyone in France was happy with the Allies’ successes. When news came of the D-Day landings, many active collaborators from the Vichy regime fled Normandy and hid in Germany. Others were publicly humiliated for their collusion with the Germans. One soldier said, “I had an experience […] in Lille in France. There were these people that went into this village and they were cutting these women’s hair off, you know, because they’d been associating with the Germans. And […] they’d just clip it all off and then they’d get a razor and make them all bald-headed” (Robert Bruce, member of the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps, Veterans Affairs Canada).

The end begins

The French people anticipated their impending liberation with excitement. In the weeks leading up to D-Day, word spread of an Allied invasion, and many people looked for signs that the rumours were true.

The reaction by the German forces to reports of an Allied invasion was a sign to French civilians that the war was not going well for their occupiers. Organizational problems hampered the German defence, and they were soon overwhelmed. After seeing the enemy overrun, and encouraged by news of the landings, many civilians realized that the end of the war was fast approaching.

However, the arrival of Allied forces did not mean good news for everyone. To liberate the Normandy coast, the American-British air force carried out many bombing raids on German-held positions. Unfortunately, many of these positions were in urban centres with large civilian populations. The Allied bombings created immense damage and caused large numbers of casualties. The French reaction to these raids was often very mixed, as they both hailed the liberators as heroes and saw them as destroyers.

The bombing of Le Havre: A Case Study

Enemy reprisals

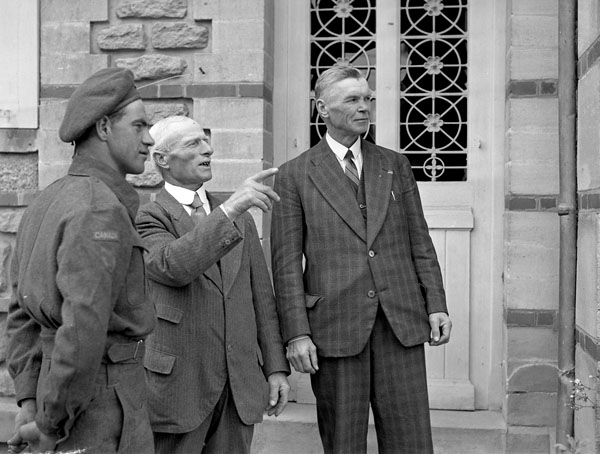

During the Allied landings, the German army brutally defended its positions and committed many war crimes in the process. Many members of the Wehrmacht stationed in France were battle-hardened veterans of the Eastern Front or Hitler Youth recruits made fanatical by the Nazi regime. This was particularly true in the case of German commander Kurt Meyer. Known for his serious war crimes in Eastern Europe, Meyer was sent to France to fight the Allied invasion.

No one was spared from the terror exacted by the Germans. During the D-Day landings on June 6, the Wehrmacht executed many Resistance fighters who were imprisoned in Caen. From June 7 to 17, 1944, the Meyer-commanded SS murdered 158 Canadian prisoners of war in Normandy. The Normandy massacres were some of the worst crimes committed against Canadian soldiers during the war. Civilians were not spared either and many villages across the country were attacked. In Oradour-sur-Glane, 643 French civilians were massacred on June 10, 1944.

Snapshots of Service

Frank Bing Wong

Proving loyalty

Biography

Frank Bing Wong was born in Vancouver in 1919 but grew up in the small fishing village of Alert Bay, British Columbia. He enlisted in 1942, saying that he saw joining the army as an opportunity to show his loyalty to Canada, and hoping that he would gain the right to vote after the war, as he, like most Chinese Canadians at the time, did not have full rights in Canada. His service in an artillery repair unit brought him to Barrie, Ontario, Scotland, and finally to Juno Beach.

Frank landed on Juno Beach about a month after D-Day, and participated in the liberation of Caen, where he said he felt ill from the sight and smell of so many corpses. He went on to participate in the liberation of the Netherlands as well. After the war, Chinese Canadian veterans fought for their rights and, in 1947, the Canadian government repealed the ban on Chinese immigration and gave Chinese Canadian citizens full enfranchisement.

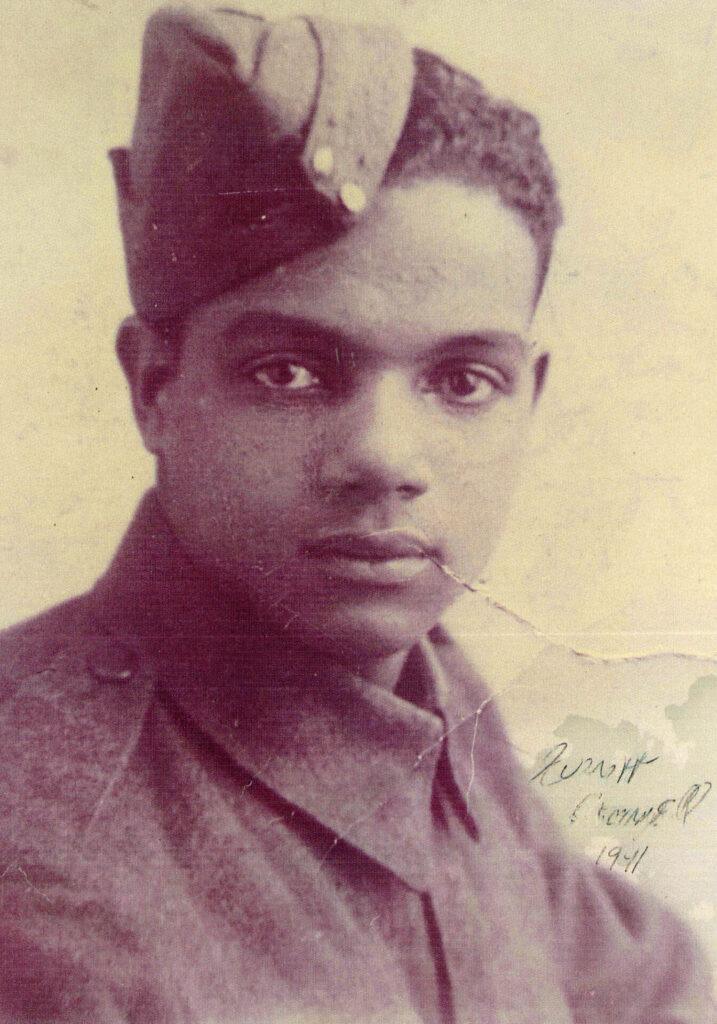

Everett Sylvester Cromwell

Munitions transport

Biography

Everett Sylvester Cromwell was born in Weymouth Falls, Nova Scotia in 1921. When WWII started in 1939, he saw the Army turning Black people away, but by the time he enrolled in 1941, he had no problems. He was put into the Royal Canadian Army Service Corp and was told he’d probably be driving vehicles, to which he replied, “I had never been inside a vehicle for a drive let alone drive one.”

After intensive training in England, however, Cromwell became an integral part of a munitions transport unit that landed on Juno Beach with 30 trucks. He and his team would load supplies off ships and drive them to the front lines, where they were in firing range of the Germans. On the return voyage, they would bring German prisoners of war back to the ships. After the war, Cromwell remained in the Canadian Armed Forces until retirement in 1971. He was also a founding member of the Black Loyalist Heritage Society in Nova Scotia.

Emilien Dufresne

Prisoner of War

Biography

Born in Gaspésie in 1923, Private Emilien Dufresne was one of many Canadians taken prisoner by the Wehrmacht during the war. After landing in Normandy with the rest of the Régiment de la Chaudière, he was captured during the night and transported across France in animal convoys, ending up in a German prison camp. It was only on April 9, 1945, when the American army arrived at the camp, that Emilien was released from captivity and able to return home. Years later, he published his memoirs Calepin d’espoir.