In the Great War we have a tendency to focus on the men with weapons performing heroic deeds and facing the enemy. Our reminisce forget there were other people besides combatants in the War. The Canadian Army Service Corps (CASC), Canadian Forestry Corps (CFC), Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC) and others played a vital role providing services to men at the front. They took care of the men’s physical needs, but our focus is the oft-forgotten group that served an entirely different function. They were there to provide spiritual and emotional support as members of the clergy.

At the outbreak of war, as young men rushed to the colours, so did men of the cloth. As part of the Canadian Chaplain Services, they went for as many reasons as the ordinary enlistees: imperialistic duty, adventure, glory, or calling. This blog will briefly examine three of these Honorary Captains.

The first thing to clear up is why they were ‘Honorary Captains’. Most simply put this was to recognize their standing in the community by treating them as officers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). The reason it is honorary is they were not part of the line of command, and had no command functions. They were treated as officers, but not as combatants. They were to act as advisors to all officers and other ranks.

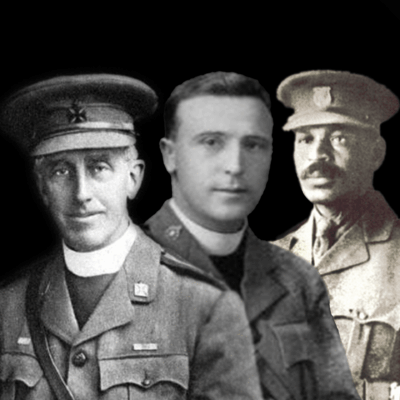

We are going to briefly look at three of the most famous Chaplains of the Great War: Canon Frederick George Scott, CMG DSO, Father Benedict Joseph Murdoch and Reverend William Andrew White. Each of these men bring with them unique perspectives on the war and their part in it. Equally importantly, they all left us a written record of their activities during the war.

There seems to exist only two full length books telling the story of the Chaplaincy during the Great War: The War as I Saw It by Scott and Red Vineyard and Part Way Through by Murdoch. For his part, Rev. White would leave us his diary and letters.

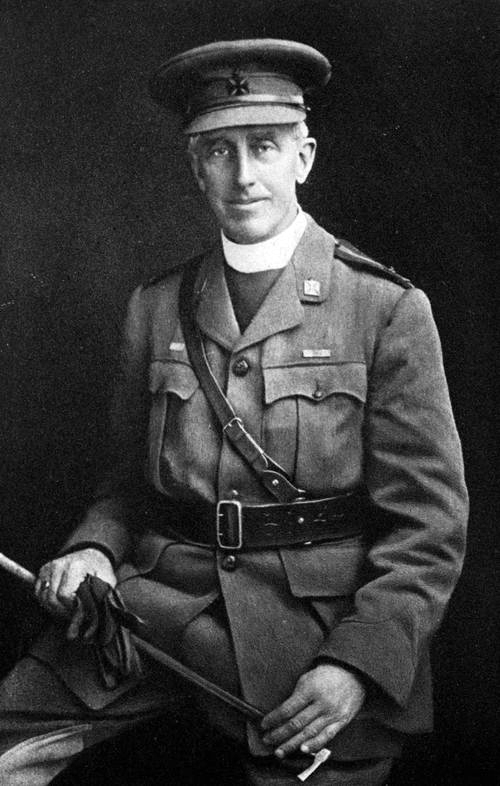

Their personal narratives are very different. Scott, an urbane Anglican Priest is an older man with sons in the CEF and a strong sense of imperial duty. He was famous for his bravery and poetry. The rural maritime Roman Catholic priest Father Murdoch is on the other hand in his twenties and joined the war not out of imperial duty, but because he had a deep belief that it was his calling to provide support and succor to the men, and intercede between them and God. The Baptist Reverend William Andrew White was prominent man of learning in the African Nova Scotian community, was to serve as Chaplain for No. 2 Construction Battalion, the only segregated Black Canadian unit. He was one of approximately seven Black men to hold a commission in the CEF. He served because his men needed him.

There are remarkable similarities in what these men did. They travelled to visit their parishioners where they worked. Talking to the men and sharing their experiences. Both Scott and Murdoch against orders spent considerable amounts of time within hearing of the guns. Often at great personal risk. As a labour battalion attached to the Canadian Forestry Corps, No. 2 Construction Battalion was to spend the majority of their war in the Jura area of France, harvesting lumber for use by the CEF. White would spend his time sharing the men’s experiences of isolation, petty politics and harsh initial living conditions. All of them listened to soldiers, comforted the sick, wrote letters back home for the illiterate, loaned small amounts to bid the men over, worried about their men, counselled them in their moments of terror and in some cases comforted them while they were dying. They were there to talk about their anxieties, doubts and horrors and to provide them with moral support. Much like the clergy for generations before them, they acted as primary mental health workers.

In some ways their experiences were unique from each other, but they also were representative of the men they served. The 53 year old son of a professor, FG Scott had seven children, of which three sons enlisted and served in Europe. The oldest, William, was a private in the Royal Montreal Regiment, and would in 1915 be blinded in one eye. Third oldest son, Rhodes Scholar Elton joined the artillery and would be severely gassed in early 1918. Most tragically, the second oldest son, Captain Henry H Scott would be killed near Regina Trench during the Battle of the Somme. Scott, himself would be Mentioned in Dispatches three times and severely wounded by shrapnel near Cambrai in late September of 1918. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his actions tending the wounded. He came out of the war as a strong supporter of the ‘civilizing power’ of British imperialism.

The 29 year old Father Murdoch was to experience all of the horrors of the war and come home with what we now would call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), or Shell Shock as it was then known. He would never truly recover from his war experience and spend most of the rest of his life living in seclusion in Bortibog, New Brunswick. He went on to author nine books. He would leave behind his written record of both his experiences serving the men at the front and his struggles with PTSD.

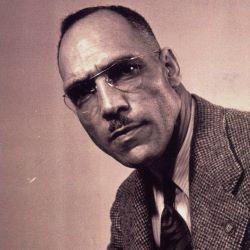

Revendend White returned home to hearth and family. He would minister to the congregation at Cornwallis Street Baptist Church, broadcast his service over the radio and become well known throughout the Maritimes. He and his beloved Izie Dora were to raise thirteen very accomplished children. In 1936, White would be the first Black Canadian to be given an Honorary Doctorate from his alma mater Acadia University.

Guest written by Kris Tozer for Honouring Bravery

Written Material of the Honorary Captains:

Murdoch, Benedict J. The Red Vineyard. 10th ed., Glascow, Robert MacLehose and Company LTD, University Press, 1959.

Scott, Frederick George. The Great War as I Saw it. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2014.

White, William A. White’s Diaries. Toronto, Toronto Metropolitan University Library, https://wardiaries.ca/s/operationcanada/page/william-andrew-white. Accessed 24 March 2025.