The history of Canadian participation in the Great War of 1914-1918 often overlooks the members of Indigenous communities who were involved in the conflict. To describe First Peoples’ participation in the war, we can look at their experiences with recruitment, the role of specific Indigenous people in the conflict, as well as the discrimination they experienced.

Recruitment

At the outbreak of the conflict, the military generally refused to recruit Indigenous volunteers, most of whom were rejected by the Canadian Expeditionary Force at the start of the war. This generalized refusal was mainly because the military was not prepared to receive volunteers from remote communities who spoke different languages and were unfamiliar with public administration practices. Racial prejudice at the time also contributed to this refusal, as First Nations volunteers were perceived as inferior soldiers.

Once the Great War had become more entrenched on the Old Continent, the armed forces showed a greater openness towards members of Indigenous communities who wanted to do their part. The need to bring more and more troops to the front finally convinced army staff not to forgo these volunteers. First Nations reserves were even contacted directly by Indian Agents to encourage people to enlist. The Six Nations Iroquois Reserve in Ontario and the Tyendinaga Mohawk Reserve in the Bay of Quinte provided the most volunteers, with the same practice applied on multiple reserves during 1917. Canadian military statistics indicate that over 4,000 First Nations people served in the war. However, historians agree that the actual number is higher because many soldiers enlisted without their Indigenous status being recorded, as some would either not declare or deliberately hide their status.

Their Role in the Fighting

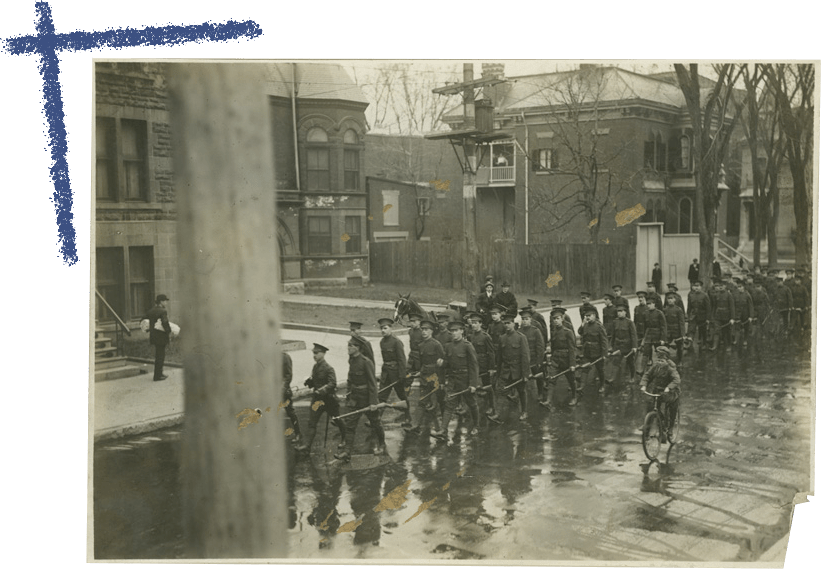

The role of Indigenous soldiers among Canadian troops at the front has been analyzed by historians such as Robert J. Talbot and Timothy C. Winegard (see end bibliography). Their analyses show that there were no units strictly for First Nations members, who were instead parachuted into various battalions. The special case of the 107th Battalion stands out for its 500 Indigenous soldiers. However, this unit did not find itself directly on the front lines, as it remained in Great Britain for a good part of the conflict. This battalion was commanded only by white officers despite its large number of Indigenous soldiers.

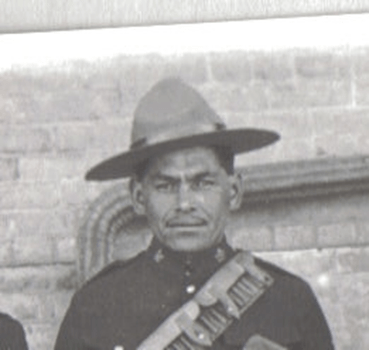

A number of Indigenous soldiers showed outstanding individual action during the conflict. One example is Ojibwa sniper Francis Pegahmagabow, who was awarded the Military Medal with two bars, a highly prestigious honour. Another is Clear Sky, from Kahnawake, Quebec, who was awarded the Military Medal for bravery in combat. We also cannot overlook Henry Norwest, a Métis-Cree, who was the most effective sniper in the entire British Empire during the Great War with kills of over 115 enemy soldiers. These cases illustrate how Indigenous Canadian soldiers were formidable on the front lines during the Great War.

Discrimination

As mentioned above, Indigenous soldiers in World War I faced prejudice and discrimination during the initial recruitment process. At the start of the war, the Canadian government and its allies feared that Indigenous soldiers would engage in scalping, battlefield torture, or other acts they deemed uncivilized. These fears stemmed from a lack of knowledge about these peoples and their customs as well as discrimination from racial prejudice, a situation that did not resolve when enlistment was opened to Indigenous soldiers in 1917. The lack of volunteer soldiers forced the hand of the Canadian government to allow Indigenous volunteers to join and make up for the drop in Canadian volunteers.

Many prejudices against First Nations soldiers persisted throughout the war. For example, they were not allowed to serve as officers during the war, as was the case with the 107th Battalion described above. Although Indigenous soldiers were allowed to participate in the war effort, they remained shut out of the decision-making process.

However, the majority of stories from Indigenous soldiers at that time show that, once they left Canada, interpersonal racism and discrimination decreased drastically. The book Aboriginal People in the Canadian military features testimonials from Indigenous soldiers who served during the war. One is from Charles Bird, who said that he didn’t witness any discrimination on the front lines. This account is in keeping with a trend observed during the Great War, in which different communities came together around a common goal, thereby reducing some of the discrimination toward First Nations people.

Contributors to the War Effort

Many Indigenous individuals overcame discrimination to join the war and make their mark in battle. Since many people don’t know about these soldiers, telling their stories helps us all better understand the situation and role of the First Nations during the First World War.

Cover photo: A mix of Indigenous and white soldiers, these men are subalterns of A Company of the 107 Battalion (source: Government of Canada).

Article originally written by Charles Taillon, Master’s candidate in history at Sherbrooke University, for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Amy Butcher (traductionsamyb.ca).

In addition:

Our activity Post-War Challenges addresses similar themes identified by historian Charles Taillon. In this educational activity, teachers and students analyze texts about how different communities faced different challenges in the aftermath of the First World War. We invite you to take a look by clicking on the image!

Sources:

- Whitney Lackenbauer et al., Les Autochtones et l’expérience militaire canadienne : une histoire, Ottawa, Ministère de la Défense nationale, 2010, 189 p. (in french).

- Maria Roxana Samson, « Les Autochtones, la Milice et le département des Affaires indiennes dans le processus de recrutement pendant la Grande Guerre 1914-1916 », Université du Québec en Outaouais, mémoire de maîtrise en sciences sociales, 2021, 138 p. (in french).

- Robert J. Talbot, « “It Would Be Best to Leave Us Alone”: First Nations Responses to the Canadian War Effort, 1914-18 », Revue d’études canadiennes, vol. 45, no. 1, 2011, pp. 90-120.

- Timothy C. Winegard, For King and Kanata: Canadian Indians and the First World War, Winnipeg, University of Manitoba Press, 2012, 240 p.

- Timothy C. Winegard, Indigenous Peoples of the British Dominions and the First World War, New York, Cambridge University Press, 2012, 312 p.