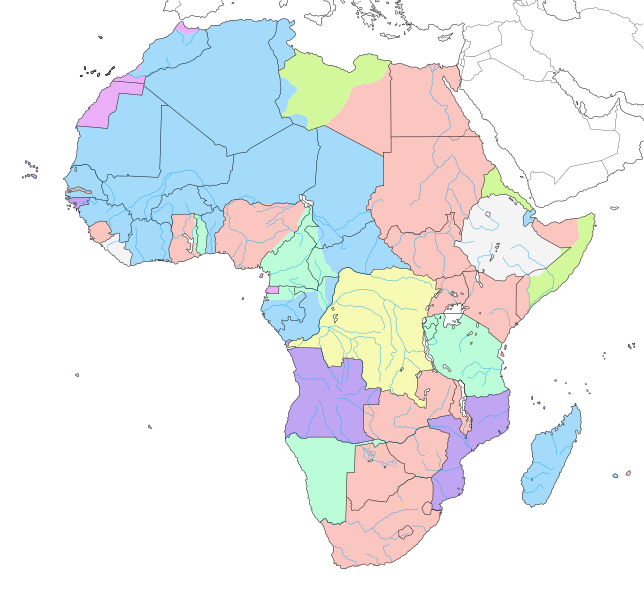

Although far from the European battlefields, the African continent was still greatly impacted by the First World War. Almost fully colonized by the end of the 19th century, Africa was both a battlefield in the conflict—particularly with the conquest of German colonies—and a site from which empires extracted material and human resources for the war effort. While some African populations found ways to resist these new and increased pressures, others saw them as a chance to gain rights by showing their loyalty to their respective empires. How the global conflict was experienced in Africa was therefore highly variable from region to region and from year to year.

The Fighting

The colonies of Togoland, Cameroon, and German South West Africa were conquered relatively quickly and without large-scale clashes. Togoland fell first after its governor tried to stay neutral, arguing that letting the African people see White men fighting would undermine the colonial order. Meanwhile, the German troops in Cameroon resisted the French, British and Belgian coalition for 15 months, and German South West Africa was conquered by the South African army in 6 months.

While these colonies fell with relative ease due to their weak military forces, the German troops in East Africa under the command of General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck fought until 1918 and only surrendered three days after the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918. Long celebrated as a tactical genius and illustrious general, Lettow-Vorbeck waged a guerrilla war that had brutal and devastating consequences on local populations. To distract the British and force them to mobilize troops in Africa, Lettow-Vorbeck and his 10,000 askaris (Black soldiers who served in the German army) pushed deep into the African bush, looting villages and forcibly conscripting people as porters, tactics emulated by the British, Portuguese and Belgians who pursued them with their own colonial troops. It is estimated that the British alone forcibly conscripted up to 1 million Africans as porters during the campaign.

Exactly how many porters and their family members died during this forced service is hard to determine, with an estimated 350,000 on the German side and probably as many for the Allies, although the British authorities cite only 95,000 deaths. The economic consequences due to destruction of the land and agriculture, forced recruitment, and systematic looting are incalculable. It is estimated that 300,000 civilians perished from this economic ruination.

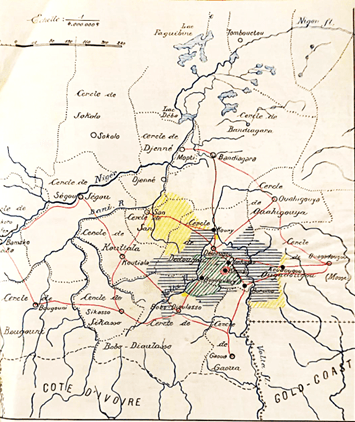

Source : ANOM, Fond Affaire politique, 1 AFFPOL 2762, Édouard Picanon, « Rapports d’ensemble sur le recrutement », Dakar, november 27, 1918, p. 87.

- Revolted zone between November 19, 1915, the date of the failure of Bouna, and December 21, the beginning of operations in Yankasso.

- Revolted zone between the failure of Yankasso on December 23 and the departure of the Molard column on February 13, 1916.

- Revolted zone after February 13, when the operations of the Molard column began.

Armed resistance

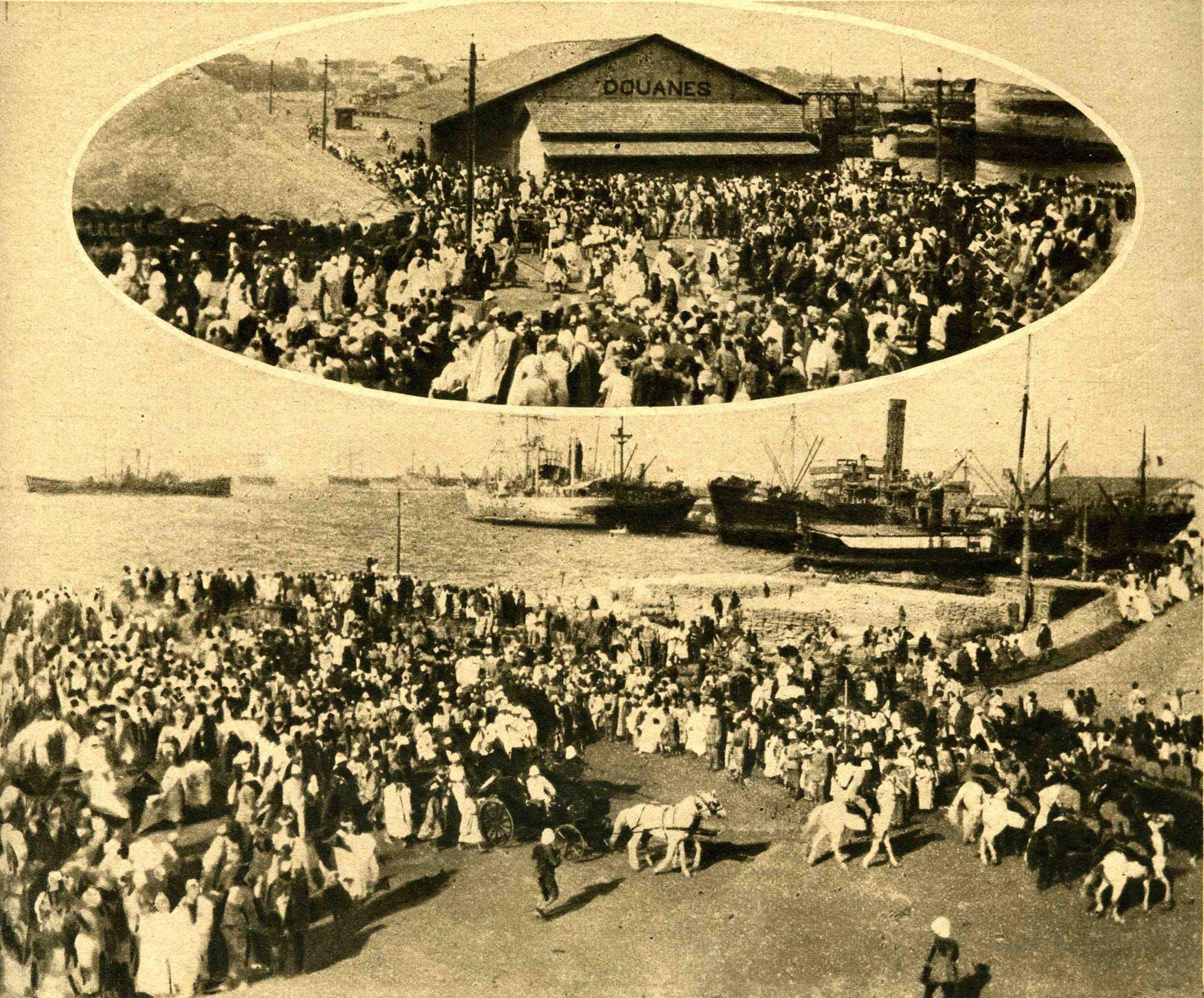

Elsewhere on the continent, fighting raged between anti-colonial movements and their respective empires, and these uprisings had multiple and varied causes. The exodus of white administrators who were recalled for military service in Europe helped create an impression of weakness throughout the colonies, while the governing States constantly increased their demands on local populations. Already poorly received by colonized peoples, the war drove up demand for men—to work and fight—and for raw materials. For example, France recruited up to 190,000 Black African soldiers to fight on many fronts in Europe and the Middle East. The porters were another example of mass mobilization. The colonizers also turned to taxation, a concept foreign to some communities that forced them into an unfavourable monetary economy. While some populations were politically sympathetic toward the Ottomans and Germans, in all cases, the colonial States were brutal and merciless in their repression. Already immensely strained by the war in Europe, these empires could not tolerate any disruption in their territories.

Revolts broke out in South Africa in 1914, when Afrikaners rallied to the German cause in reaction to their government’s support for the Allies. Islamic uprisings, sometimes incited by the Ottoman Empire’s call for jihad, sprouted up across the Sahel throughout the war. Millenarian and apocalyptic movements, such as the Watch Tower movement in Rhodesia, also destabilized the colonial order in Africa. Some anticolonial movements would rise against forced conscription. Indeed, at the start of the war, Republican France decided to involve its colonial troops in the war effort in Europe, a practice that both the British and Germans eschewed, as they had no desire to see men of colour fighting White men on the front lines. French recruitment practices were so coercive, they it seemed like a “hunt” reminiscent of what happened during slavery. The people in these communities resisted by fleeing from recruiters, presenting the oldest and weakest men, or massively migrating to British colonies where they believed they would not be enlisted. In modern-day Burkina Faso, a village coalition revolted against the French empire in November 1915 for over 9 months. A total of 30,000 anti-colonial fighters were killed over resistance to recruitment efforts during this specific conflict.

Strategic alliances

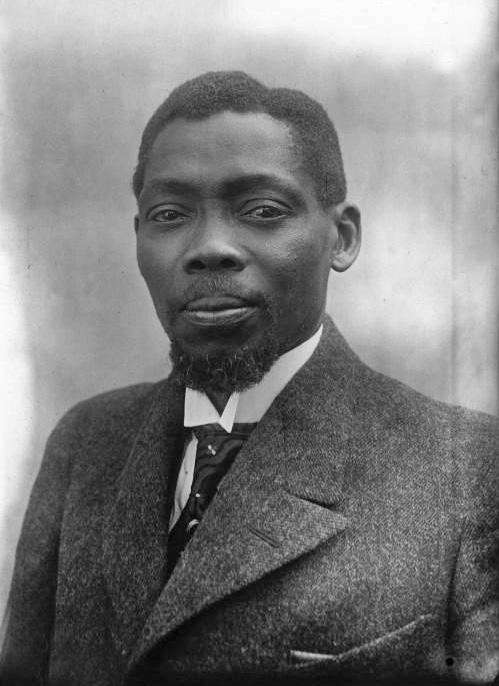

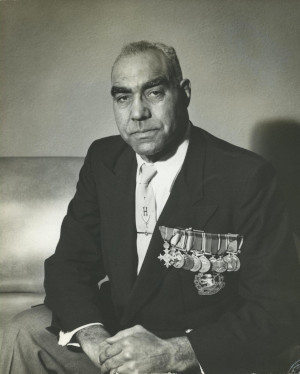

While many Africans took the road of resistance, others saw the war as a chance to prove themselves to their respective empires to gain more rights and power in the colonial political and administrative space. In most cases, these hopes were dashed. For example, representative Blaise Diagne, the first Black person to sit in the French Chamber of Deputies, was promised social and political reforms in Senegal in exchange for a campaign to recruit riflemen after the revolt in Burkina Faso. Diagne managed to rally 63,000 men, or much more than the requested 40,000. But the promised reforms never came about. The same tactic was used to recruit men into the colonial army: they were promised more rights, and even citizenship, if they signed up and paid the “blood tax.” Once again, these promises went unfulfilled.

Yet the First World War did give rise to nationalist movements and political revolts all over the continent. African elites frustrated with false promises increasingly rose up against the hypocrisy and contradictions of the colonial regimes. These movements laid the foundations for decolonization in the following decades.

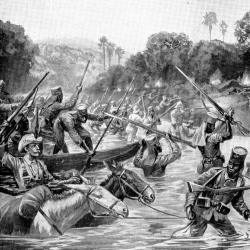

Cover photo: The battle of Ngomano in November 1917, by Author unknown (source: Wiki Commons).

Article originally written by Thomas Vennes, PhD candidate in history at Sherbrooke University, for Je Me Souviens. Translated by Amy Butcher (traductionsamyb.ca). This article is the second part of a two-part series on the First World War outside of Europe. To read the first part on the different fronts conducted in East and South Asia, you can click on the link here.

Sources:

- “Grande Guerre : les batailles oubliées de l’Afrique“, webdoc.rfi.fr (in french).

- “L’Afrique et la Première Guerre mondiale“, L’Histoire.fr (in french).

- “La tournée de Blaise Diagne“, Histoire et mémoires d’Afrique – Université Sherbrooke (in french).

- “Resistance and Rebellions (Africa)“, International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

For a more academic approach:

- Michael Crowder, “La Première Guerre mondiale et ses conséquences”, Albert Adu Boahen (dir.), Histoire générale de l’Afrique. L’Afrique sous domination coloniale, 1880 – 1935. vol. 7, Paris, Unesco/NEA, 1987, p. 307‑337 (in french).

- Richard Standish Fogarty, Race and War in France: Colonial Subjects in the French Army, 1914-1918, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008, 374 p.

- Jacques Frémeaux, Les Colonies dans la Grande Guerre: combats et épreuves des peuples d’outre-Mer, Soteca, 14-18 Éditions, 2006, 393 p. (in french).

- Marc Michel, L’Afrique dans l’engrenage de la Grande Guerre, 1914-1918, Paris, Karthala, 2013, 237 p. (in french).

- Bill Nasson, “L’Afrique”, Jay Winter (dir.), La Première Guerre Mondiale : Combats, Paris, Fayard, 2014, pp. 475‑501 (in french).

- Edward Paice, Tip and run: the untold tragedy of the Great War in Africa, Londres, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2007, 488 p.