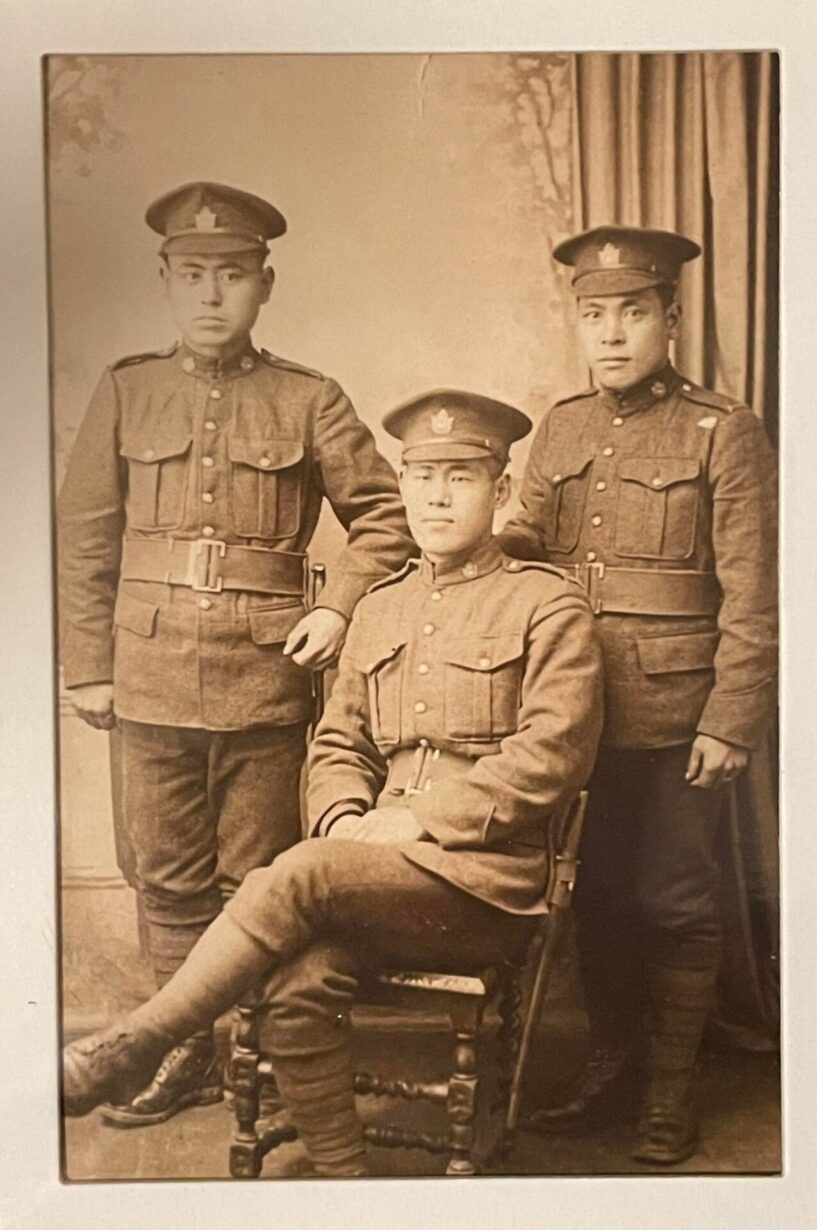

Private Nuinosuke Joseph Okawa was born on July 24, 1884 in Shizuoka, Japan and arrived in Canada in 1907 at the age of 23. He had served for six years in the Imperial Japanese Army and was a veteran of the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05). He worked as a carpenter in Vernon, British Columbia. At the outbreak of the First World War, he wanted to enlist in the army to fight alongside other Canadians. Anti-Asian racism, however, was rampant in British Columbia so Okawa had to travel all the way to Alberta to join the army. He enlisted in Calgary on August 7, 1916. He was among 196 original Japanese Canadian volunteers, joining the 192nd Battalion. During this time, Japan and the United Kingdom were allies under the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902. Its overseas subjects were eager to prove their mettle and loyalty to the King. Japanese Canadians were also seeking equal treatment in Canadian society upon their return from the battlefields. They were paid lower wages, could not work in the higher professions like medicine or law, and did not have the right to vote. Once he reached England, Okawa was transferred to the 10th Battalion on October 11, 1916 and left for France seven weeks later. Okawa fought at and survived the Battle of Vimy Ridge, later writing home about it:

“At 4:30 in the afternoon of April 8, we started our march of five miles toward Vimy Ridge. The enemy pounded our communication trenches with artillery, even using poison gas shells. It was a very difficult march, but no one was injured. By 2 a.m. we were in the forward lines. We were given rum. On the 9th at 5 a.m. our artillery started a terrific bombardment, and we went over the top. We captured 700 prisoners. The battle was over by the 11th. Our casualties were about 500 men killed and wounded. Two Japanese volunteers were killed, Pte Iwakichi Kojima [April 9] and Pte Kiyogi Migita [April 11].” 1

However, he was unlucky on August 17, 1917, at Lens, when he suffered a gunshot wound to the left arm, resulting in a compound fracture to his ulna. This injury would spell the end of Okawa’s war as he was invalided to Canada on December 31, 1917 and deemed medically unfit for further service.

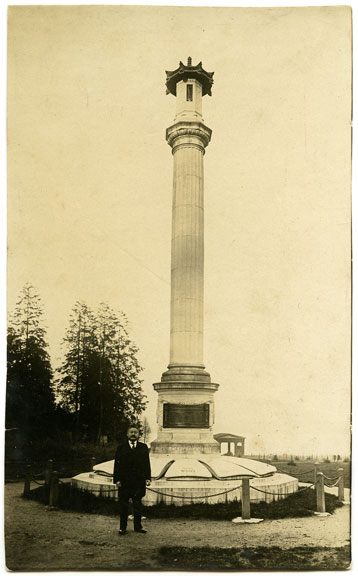

Okawa married Toku Okawa in 1919 and had two daughters. On April 9, 1920, on the third anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge, surviving veterans proudly attended the unveiling of the Japanese Canadian War Memorial in Stanley Park, Vancouver. The following year, he became a naturalized British subject. In 1927, he commissioned a fish packer to be built for him. It was a 34 foot-long, single deck vessel. He named her “Point Ose” after a small fishing village near his birthplace. He used it to transport fish in the Gulf area to canneries like Deep Bay Cannery on Vancouver Island.

What is kind of boat is a packer?

A comparatively large boat that collects the fish caught by smaller fishing boats and packs them in ice for taking to canneries or market. This saves the time of the gillnetters from going all the way back to shore when they could just offload their catch to a packer.

Taka IV (left) and Kasaska (right) are both examples of packers (Delta Museum and Archives).

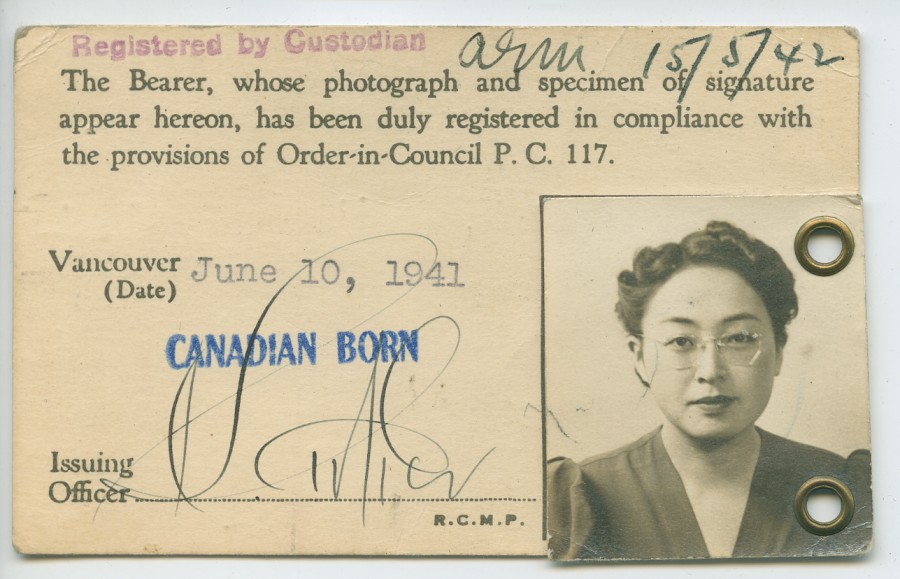

In 1931, after years of lobbying, the returned Japanese Canadian soldiers finally won their hard fought battle. Members of the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia narrowly passed –by a margin of one vote, the bill granting voting rights to all remaining Japanese Canadians veterans (but not to their wives and children). This victory, however, would only last a mere ten years. Curiously, nine months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, all members of the Japanese race residing in BC were ordered by the federal government to get registered and finger[1]printed including those born in Canada. They were ordered to carry these identification cards at all times. Then the events of December 7, 1941 complicated things when the Imperial Japanese Air Force attacked Hawaii. Under the guise of protecting Canada from disloyal traitors, racist BC politicians and members of the Anti-Asiatic League swayed Prime Minister Mackenzie King to rid the province of British Columbia’s “Japanese Problem”. Despite the RCMP’s assurance that Japanese Canadians were not a threat to national security, mass “evacuation” started in early 1942. Under the War Measures Act, 22,000 Japanese Canadians, two thirds of whom were born in Canada, along with Okawa and his family, were forcibly uprooted from all parts of coastal BC, placed in horse stalls at Hastings Park (where the Pacific National Exhibition is held annually) and finally transported to old mining ghost towns hastily converted into internment camps. The Okawas ended up in Greenwood, BC. Despite being a First World War veteran, he was incarcerated (along with nine other veterans) in squalid conditions for three and a half years.

In early 1942, the federal government began selling off the 1,137 fishing vessels that had been rounded up and confiscated in December of 1941 without the knowledge of their owners who were interned. Records show that the Point Ose was valued at $2,000. Fishing packing was Okawa’s livelihood and only source of income. The boat was sold to a John Heal for $550. After “supervision costs”, Okawa received only $407.31. By 1943, mass auctions were taking place all over the Lower Mainland of BC, selling all the contents of Japanese Canadians’ homes, personal belongings, cameras, radios, pianos, cars, houses, greenhouses, farms, businesses, parcels of land and timber rights far below fair market value. At war’s end, the Okawa family relocated to Hamilton, ON to start life anew once they were released from Greenwood. No Japanese Canadian was allowed to move back to the BC coast until the ban was lifted on April 1, 1949. Unlike in the United States when Japanese American internees were returning home in 1944, Canada’s harsh ruling of the “East of the Rockies or Japan” betrayed itself by calling the internment and dispossession, wartime measures.

In 1948, Japanese Canadians were given a chance to make claims under the Bird Commission if they felt that their property was sold at unfair prices, which they were. Mrs. Toku Okawa represented her husband at the hearing in an effort to claim some funds he lost when his boat was sold at less than a third of its value, without his consent. It is interesting to note some curious dialogue exchanged on the topic of Private Okawa’s status as a veteran.

Okawa never saw the Point Ose again and passed away on April 14, 1972 in Toronto at the age of 88. Sadly, he did not live long enough to witness the apology and redress in 1988 by Prime Minister Mulroney. My passion to bring to light the history and plight of Japanese Canadians who fought in the First World War coupled with the launch of UVic’s Landscapes of Injustice Archive enabled me to research what happened to these soldiers after 1918. As I had speculated, dozens of war veterans interned, dispossessed and even exiled to Japan in 1946. I created a Facebook Group in 2022 called Japanese Canadian Fishing Boats. My goal is to reunite Japanese Canadians with their family’s lost fishing vessels, if only through photographs. After growing the membership to almost 400 people comprised of a mix of white fishermen and descendants of Japanese Canadian fishermen, a match was made when a group member, Ross Holkestad posted a photo he had come across online of the Point Ose! George Takahashi, also a group member and grandson of Private Nuinosuke Okawa, had never seen a photo of his grandfather’s boat before and was thrilled to finally “meet” her.

I was extremely happy that some form of closure has been given to the Okawa family – this family that was “twice sacrificed” deserves this gift of a find. Thank you for your service, Private Okawa, Vimy Ridge hero–Enemy Alien – the irony is not lost on me. Rest easy, the Point Ose has been found and reunited.

Lest we forget.

Article guest written by Debbie Jiang for Honouring Bravery.

- Ito, Roy, We Went to War. (Stittsville, ON: Canada’s Wings, Inc. 1984), page 62 ↩︎