The landings

The Plan

After successes in North Africa, Italy and Stalingrad, the Allies turned their attention towards France. The Allies knew the liberation of France was a crucial step to defeat the Nazis. The plan to land in Normandy to begin this liberation was approved at the Quebec Conference in August 1943 and given the codename “Operation Overlord”.

Through their eyes

“I just heard about D-Day, I think it was […] maybe March or April, 1944, when […] a messenger brought an envelope to me. And it had great red letters on it, “Top Secret, Commander’s Eyes Only.” And I had no business even knowing about such a thing. […] And I put it on my boss’s desk and covered it over because it was top secret. […] And when he came back, he said: ‘Where the hell did you get this?’ So I said: ‘Well, a messenger dropped it.’ […] and he was really quite angry: ‘just forget you’ve ever ever laid eyes on it, put it on the safe and forget it.’”

—Ruth St. Clair (1925-2014), member of the Women’s Royal Naval Service (courtesy of Historica Canada).

Deception

German Forces believed that an allied invasion of France would likely occur 240 kilometers away from the beaches of Normandy near Pas-de-Calais. This was because Pas-de-Calais provided a faster and more direct route from England to France, via the Dover Strait. Allied leadership used this to their advantage by performing a series of deceptions (codenamed Operation Fortitude) to trick German forces into thinking that the invasion was indeed going to happen at Pas-de-Calais, rather than in Normandy. To help in this deception, Allied forces staged a fake army in Dover, England leading up to D-Day. This included using inflatable tanks, wooden airplanes and dummy landing crafts. The plan worked and the fake invasion force diverted many German units away from Normandy.

D-Day

After nearly a year of planning, the Normandy landings occurred on June 6, 1944. The operation encompassed a massive air, navy and armoured-vehicle assault on the German defences and Canadian soldiers played an important role alongside American and British troops. The landings became an important historical moment, as they marked the beginning of the end of the war. Participation in the landings is therefore a source of pride for many Canadians.

“It was the greatest event in the history of our lifetimes, there’s no doubt about that. And there will probably never be anything like that again. When you consider D-Day, it was the greatest armada in the history of mankind. Going over to Normandy. […] On the early hours of 6 June, I was on duty and I heard this roar of planes going over. I looked up in the sky and it was dozens of planes towing gliders. So obviously D-Day had begun.”

—Roy Halford, soldier of the Royal Berkshire Regiment, courtesy of Historica Canada.

The Beaches of Normandy

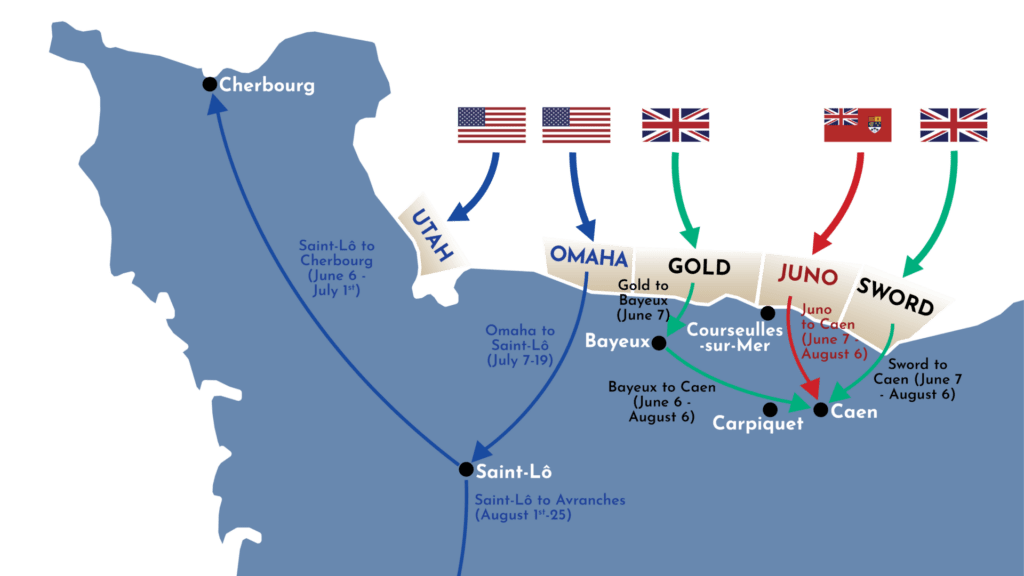

As part of the invasion, the Allies divided the coast of Normandy into five landing zones. Canadians were tasked with landing on Juno Beach: a nearly 10 kilometer stretch of beachfront near the village of Courseulles-sur-Mer.

A map of the Beaches of Normandy. Arrows indicate the movement of forces after the landing.

Think: Using the following images as a starting point, what factors might have been important while planning for the landings? What obstacles might have participants prepared for?

Did you know?

The first house to be liberated by the Canadians still exists today. Just steps from the beach, members of The Queen’s Own Rifles liberated the house within 20 minutes of landing on the beach. Since then, the building (now known as Canada House) became an important symbol of D-Day and a place to remember those who died during the Normandy Landings. Click here to learn more.

By the Numbers

The Normandy landing was the largest combined air, naval and land operation in history. This infographic shows Canada’s participation in the operation.

Snapshots of service

Sheila Elizabeth Whitton

Wren coder

Biography

Born in Toronto on October 25, 1922 Sheila Elizabeth Whitton enlisted in the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service. She was stationed in Halifax and became a coder. In preparation for the D-Day invasion, she was sent to England in April 1944 where she worked on codes that helped to make the invasion successful. Shortly after arriving in England, she married her long-time boyfriend Robert Fleming, who was serving overseas with the Queen’s Own Rifles. Sadly Robert died shortly after D-Day on June 11th, leaving Sheila a widow.

Lester Brown

Last Black D-Day Veteran

Biography

Lester ‘Bub’ Brown was drafted into the Canadian Army when he was 23 and took part in the Normandy Invasion with the Queen’s Own Rifles. Although he made it past the beach without injury, he was wounded in both the knee and chin while helping to take the town of Bretteville-sur-laize. After the war, he worked as a railway porter and conductor for the Canadian Pacific Railway. At the time of his death in 2013, he was considered the last Black Canadian to take part in the D-Day invasions.

James “Stocky” Edwards

D-Day pilot

Biography

James Francis “Stocky” Edwards was born in Nokomis, Saskatchewan in 1921. He enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1940 and, after completing his training in England, became one of the rare Allied pilots to fight in all of the major Allied campaigns: the North African, Italian and North-West Europe campaigns. His record includes shooting down 19 enemy aircraft (plus 7 more “probables”) and destroying 12 aircraft and 200 vehicles on the ground. He was considered a flying ace and one of the Commonwealth’s top fighter pilots. Promoted to squadron leader after his actions in Italy, he and his team flew in support of the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944. Edwards remained in the RCAF until his retirement in 1972.