Becoming Nurses

Image courtesy of the Toronto Public Library

During the mid 19th century hospitals recruited mostly poor and uneducated women to become nurses. Consequently, although basic patient care was considered a woman’s role, many people did not see nursing as a respectable career. Florence Nightingale changed all of this by inspiring women to become nurses and setting the stage for formal education and practice. By 1905, sixty-five schools across Canada offered training programs for nurses. Unfortunately, low salaries and poor working conditions made the recruitment and the retention of nurses very difficult. Moreover, most women felt pressured to leave their nursing career as soon as they got married.

Think: Why might someone want to become a nurse during wartime? What traits might help them succeed?

A timeline of nursing

Indigenous medicine

Long before Europeans arrived in Canada, Indigenous peoples cared for their sick using their own medical practices. Traditional Indigenous medicine is still practiced by many Indigenous peoples today.

Image: Indigenous Medicine Wheel

Early Nursing

In 1639 Augustine Nuns opened North America’s first hospital in Quebec City (the Hotel-Dieu). Religious and charitable organizations remained the main provider of healthcare in Canada for centuries.

Image: Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec (Archives of Montreal)

Florence Nightengale

In 1854 Florence Nightengale arrived in Constantinople after the British government asked her to train nurses in the Crimean War. She found the military hospital in dismal condition and quickly improved the survival rate of patients using her methods of nursing. After the war, she founded the Nightengale training School for Nurses and became a trailblazer in professionalizing the nursing profession.

Image: Florence Nightengale (Wellcome Collection)

Canada’s first nursing school

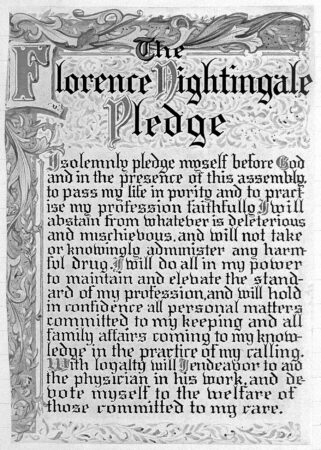

The Mack training School opened at the General Hospital in St. Catherines, Ontario in 1874. Based on Florence Nightengale’s model, it became Canada’s first nursing school. At the end of their training, graduating nurses had to take the Nightengale’s pledge. Unfortunately, women of colour were not permitted to join nursing schools in Canada until the late 1940s.

Image: Florence Nightengale Pledge (Wellcome Collection)

Armed Conflict

Canadian nurses first officially took part in an armed conflict during the Northwest Rebellion (1885). Twelve Canadian Nurses also served in the Boer War in South Africa in 1899.

Image: The Battle of Cut Knife (Library and Archives Canada)

Boer War

In 1901, the Canadian Army Medical Corps officially integrated military nurses as part of its effective strength. Canada became the first country where nurses received formal military recognition, including a rank and pay.

Image: Nurse Minnie Affleck with Soldiers during the Boer War (Library and Archives Canada)

“I solemnly pledge myself before God and in the presence of this assembly to pass my life in purity and to practise my profession faithfully. I will abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous, and will not take or knowingly administer any harmful drug. I will do all in my power to maintain and elevate the standard of my profession, and will hold in confidence all personal matters committed to my keeping and all family affairs coming to my knowledge in the practice of my calling. With loyalty will I endeavour to aid the physicians in his work, and devote myself to the welfare of those committed to my care.”

—The Florence Nightingale Pledge

Equal Rank and Pay

During both World Wars, Canada was the only country where nurses were fully enlisted officers in the Armed Forces. In WWI, a Canadian Army nurse was granted the rank of Lieutenant and earned $2.00 a day. This was double what a of a Private made in the trenches, and was four times what many nurses were earning working at hospitals in urban centres.

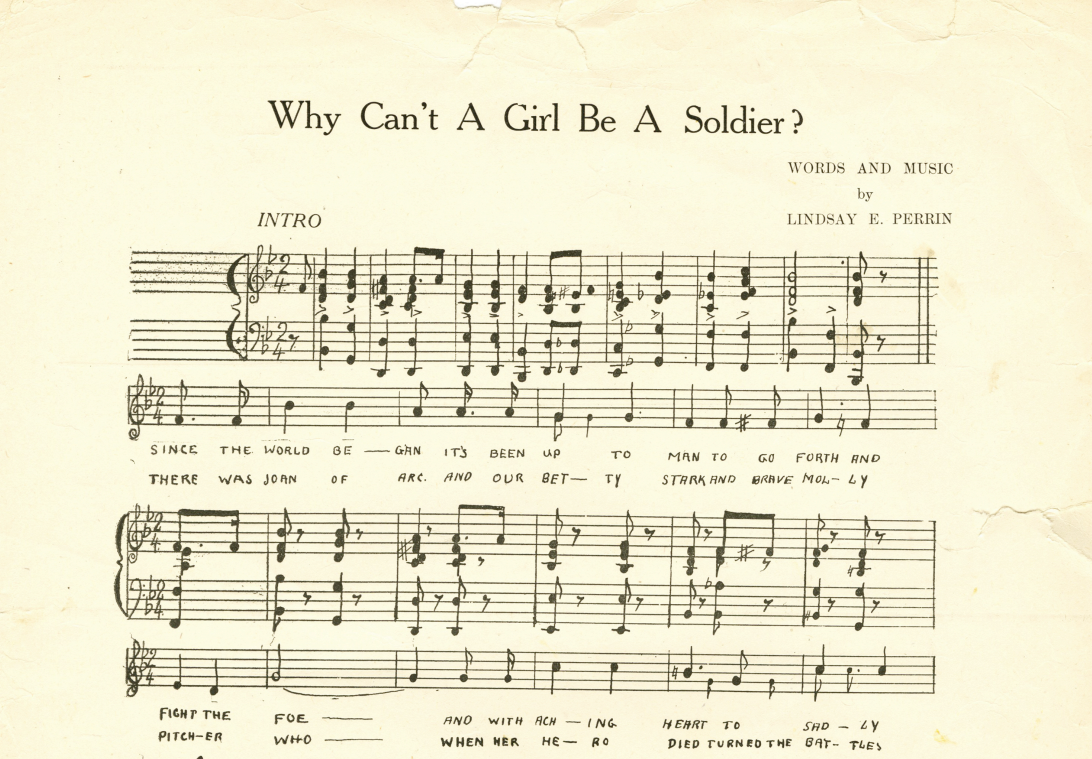

Listen: Click here to hear the song “Why Can’t A Girl be A Soldier”. Why might have this song been so popular?

To listen to click here.

Multiple Identities

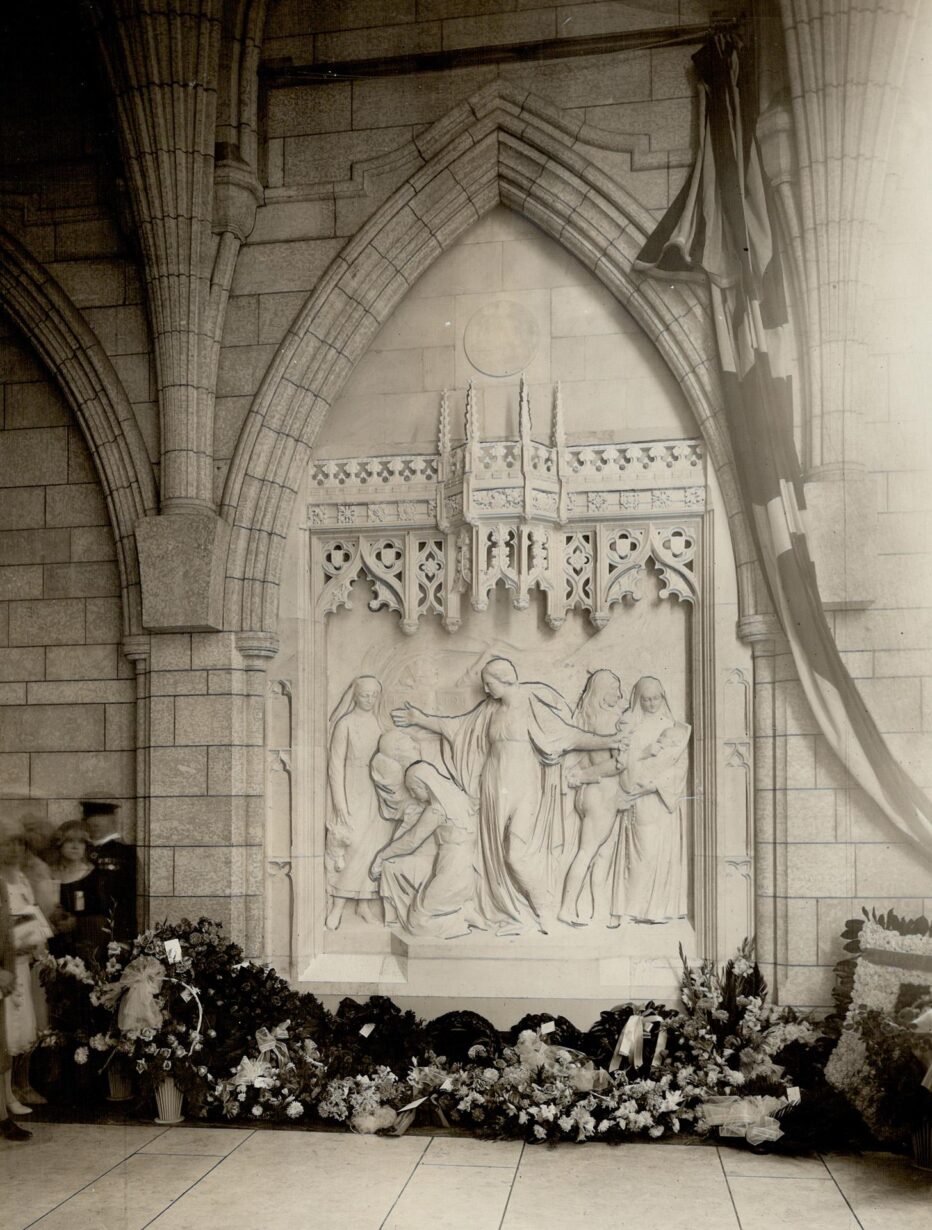

As all nurses were women and most were single, a number of stereotypes emerged around nurses. Nurses were portrayed as saintly, matronly and ideallic, which was reinforced by patients who were greatful for the caregiving they received. They affectionately nicknamed the nurses “Sisters of Mercy” or “Angels of Mercy”. Nursing sisters were also admired for their courage as well as their compassion. Many nurses returned to Canada with a new sense of pride and their actions overseas helped support the importance of women participating in a changing Canadian socitey. A memorial to the nursing sisters of the First World War was erected in Ottawa in 1926 in the Hall of Honour in the Parliament of Canada.

Nurses volunteered for service out of patriotism and a desire to care for others. They may not have supported the concept of war, but, as in any disaster, they saw the need to be there to care for the victims of this conflict. The only women present at the Casualty clearing stations close to the front were nurses. For wounded soldiers, nurses provided emotional and moral support, and became individuals whom they could confide their hopes and fears. Many families were comforted by the letters that the nurses wrote on behalf of the wounded in their final days.

Women who volunteered during the war served under many banners. Some volunteers were trained professionals, while others had limited training, such as those in Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs). Some enlisted in the Armed Services, while others were attached to organizations, like the Red Cross. Coordination of all their efforts to work as a team was no doubt a difficult and trying experience. Nursing sisters of the Canadian Expeditionary Force were trained professionals and were under the direct control of the army.

Nurses volunteered for service out of patriotism and a desire to care for others. They may not have supported the concept of war, but, as in any disaster, they saw the need to be there to care for the victims of this conflict.The only women present at the Casualty clearing stations close to the front were nurses. For wounded soldiers, nurses provided emotional and moral support, and became individuals whom they could confide their hopes and fears. Many families were comforted by the letters that the nurses wrote on behalf of the wounded in their final days.

Did you know?

Not all VAD volunteers who volunteered overseas became nurses. At a time when driving was still predominately an activity for men, women like Grace MacPherson of Vancouver broke traditional gender roles and became ambulance drivers. These women not only drove the ambulances, but helped repair the fleet.

Image: Grace MacPherson (Library and Archives Canada)

The circumstances of war limited the chance of social activities. With the rank of Lieutenant, Canadian Nursing Sisters in uniform could only socialize with officers, while British nurses, conversely, could only socialize with the rank and file. Nurses at stationary hospitals organized various social events for the soldiers, but fraternization was not encouraged outside of work or these events. Nurses and soldiers also had different regulations relating to marriage and home leave. Women could be given permission to return home to take care of family issues, while the men were obliged to remain at the front.

Through their eyes

Lenora Herrington

Recipient of the Military Medal

Biography

Lenora Herrington was born near Ameliasburg, Ontario in 1873. At 39, she graduated from nursing school in Winnipeg and enlisted three years later in 1915. She was working as the night superintendent at the No.1 Canadian General Hospital when, on May 31, 1918, the hospital was attacked during an air raid. According to her medal citation, “she bravely remained on duty throughout the night and “by her excellent example and personal courage was largely responsible for the maintenance of discipline and efficiency.” For her bravery and devotion to her duties, she was awarded the Military Medal. She is one of only nine Canadian women to have received this medal during the war. After the war, she worked at the Queen’s military Hospital in Kingston in the Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment department.

Elizabeth Smellie

Canada’s first female Colonel

Biography

Born in 1884 in Port Arthur Ontario, Elizabeth Smellie graduated from Johns Hopkins School of Nursing in 1909. She was one of the first volunteers of the nursing section of the Medical Corps. During the war, she worked as a night supervisor and later became the matron at Moore Barracks Hospital in Shorncliffe. For her excellent service, she was given the Royal Red Cross, First Class. After the war, she taught at McGill University and later became the Chief superintendent of the Victorian Order of Nurses in Canada. Later, during the Second World War, she reenlisted and helped organize the Canadian Women’s Army corps. In 1944, she became the first woman in Canada to become a Colonel.

Murney Pugh and Ellanore Parker

The “Heavenly Twins”

Biography

Murney Pugh was born in Kingston, Ontario in 1882. In 1914, she went overseas as a Nursing Sister. In 1915 she met her life partner and fellow nurse Ellanore Parker. Ellanore was born in Ireland, but trained as a nurse at the Winnipeg General Hospital. The pair met while they were both stationed at a hospital in England. Murney and Ellanore worked together treating soldiers at military hospitals in England and France. While in France, both Murney and Ellanore suffered the effects of gas poisoning while treating soldiers who were exposed to the gas attacks at the Somme and Vimy Ridge. Although Murney recovered, Ellanore suffered health problems for the rest of her life. After the war, they settled in Los Angeles and Ellanore became an author and inventor. In 1948, they moved back to Canada and lived together in Victoria for the rest of their lives.