My family displays a number of important photographs in our front hallway. Some of those images depict Elizabeth Langman, an ancestor on my husband’s side of the family. Great Aunt Elizabeth served as a nursing sister in Africa and Italy during the Second World War. Aside from these photographs, we don’t know very much about what she did because she didn’t talk about it upon her return. But we knew she was brave, and the photographs are a way of honouring that bravery.

As an immigrant of Chinese heritage, I assumed there was not much to know about the contributions of Chinese Canadians to early Canadian history beyond the construction of the railroad. After construction was completed, Head Taxes and The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 severely limited the rights of Canadians of Chinese heritage. The Act wasn’t repealed until 1947 and during the years that it was in effect, fewer than 50 immigrants of Chinese heritage were admitted to Canada.

As a student and then teacher in Ontario, I learned nothing about Chinese contributions to the war effort in Canada. When my husband and I had our son, I was able to tell him about Aunt Elizabeth and other brave people from his father’s side of the family. He even completed a history project about his Great Great Great Uncle, Private William Harry Little (1890-1918), who served with the 38th Infantry Battalion and died after being injured during the battle for the main Douai-Cabrai Road in France. However, sometime in the lead up to Remembrance Day in 2017, I learned about Force 136 for the first time through a CBC article and then through a documentary called Force 136: Chinese Canadian Heroes.

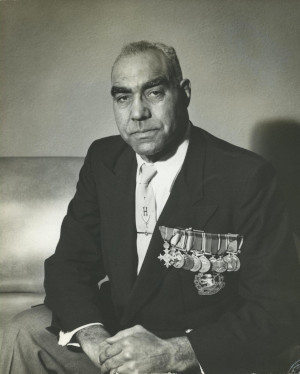

I remember reading the CBC article that quoted Veteran Ronald Lee as he told stories from “his Second World War ‘adventure’ in Burma as part of a dangerous and secret British-led operation. Ronald Lee went on to describe a Canada that didn’t allow Chinese-Canadians into university so they couldn’t enter the professions to become teachers, doctors or lawyers. He described being treated as a second-class citizen. But despite these things, the young man from a family of five boys from Vancouver’s Chinatown volunteered for Force 136.

“When I wanted to enter the army in Canada I was refused. At that time they did not take any Chinese – Canadians in the armed forces.”

— Ronald Lee quoted in Force 136: Chinese-Canadian veteran reflects on service in special forces unit

Born on March 4, 1919, Lee was in his early 20s when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. After that fateful day in December 1941, the Allied Forces suffered major losses in Southeast Asia and realized they needed the men of Chinese heritage from Canada.

Young men like Lee had the ability to speak English and local Chinese dialects. Unlike other recruits, they would blend seamlessly into the local population. This made them ideal candidates to train for sabotage and intelligence missions.

Force 136 members were trained in various locations around the world. Lee did basic training in Chilliwack, British Columbia before travelling to England, Cairo, Bombay (known today as Mumbai), Calcutta (known today as Kolkata) and Ceylon (known today as Sri Lanka). In addition to being trained in guerrilla warfare tactics, he received extra training to specialize as a wireless operator.

Lee described being issued two specific items in his kit before deployment. He was given an opium pill and cyanide pill. The first could prove helpful for trading and the second was to be used in case of capture. Lee was scheduled to be parachuted into Burma (now known as Myanmar) for a mission he would have been unlikely to survive when the U.S. dropped atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

When the war ended, Lee returned home along with his unit. He became part of the Chinese – Canadian movement to lobby the Canadian government for the right to vote. It took until 1947 before Canada allowed Chinese-Canadians to vote.

Ronald Lee died at home in Vancouver on December 6, 2020 months after celebrating his 101st birthday with all 6 of his children. In 2021, I read about Ronald Lee again. The Globe and Mail article stated that Mr. Lee’s family hadn’t known about his involvement in Force 136 and, although he kept images of his time with the Force in his wallet, his family only found out about the photos after the wallet was lost and later returned to the family.

My curiosity was piqued as I didn’t recall learning anything about Chinese Canadian efforts in the Second World War as part of my studies. These two events stayed with me as I transitioned from a career in education to one as a picture book writer. I embarked on a mission to learn what I could about Force 136 but it wasn’t easy. The mission was classified and like many veterans, the members didn’t say much about it to their families.

Ontario members of Force 136

While the majority of the members of Force 136 were from the west, some were from Ontario. The following list* represents the Force 136 members identified as being from Ontario thus far. This list is not exhaustive, meaning more men from Ontario may be discovered with further research.

Frank Chin, Lucknow

James Chin, Lucknow

Billie Hong, Brockville

Fred Hong, Windsor

George Hong, Windsor

King Lewis Chow Hing, Sault Sainte Marie

Jolly Howe, Streetsville

Henry Ing, Kingston

Ben Lee, Windsor

James Lee, Brantford

Jim Lee, Wingham

Peter Lee, Windsor

Robert Soo, Oshawa

William Soo, Oshawa

Howard Soong, Ottawa

Peter Wing, Welland

George Edward Wong, London

Hin Ming “Norman” Wong, London

Nin Nge “Henry” Wong, London

William Andrew Wong, London

*List compiled by Col. (ret’d.) Chris Weicker. Used with permission.

What we do know is this: Force 136 was an international effort run as a branch of the British Special Operations Executive during the Second World War. The plan was to train the group to operate behind enemy lines. About 150 men from Canada volunteered for the mission despite the dangers. They were hopeful it would demonstrate their loyalty to Canada and help them win the rights of citizenship for themselves and their families.

The men endured rigorous training, and some were deployed on test missions, but the war ended just before many of the men were to be deployed. Some assisted with liberating prisoners of war. Some were abandoned and left to find their way back to Canada on their own.

The Canadian Force 136 Story is still being uncovered. While I don’t know of any family connections to the brave men of Force 136, I wanted to tell a story that would capture the spirit of learning about the mission for the first time.

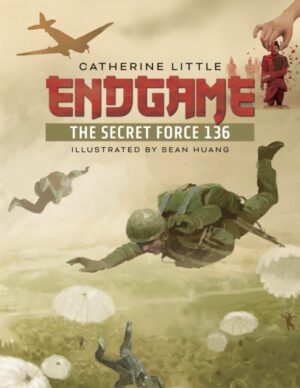

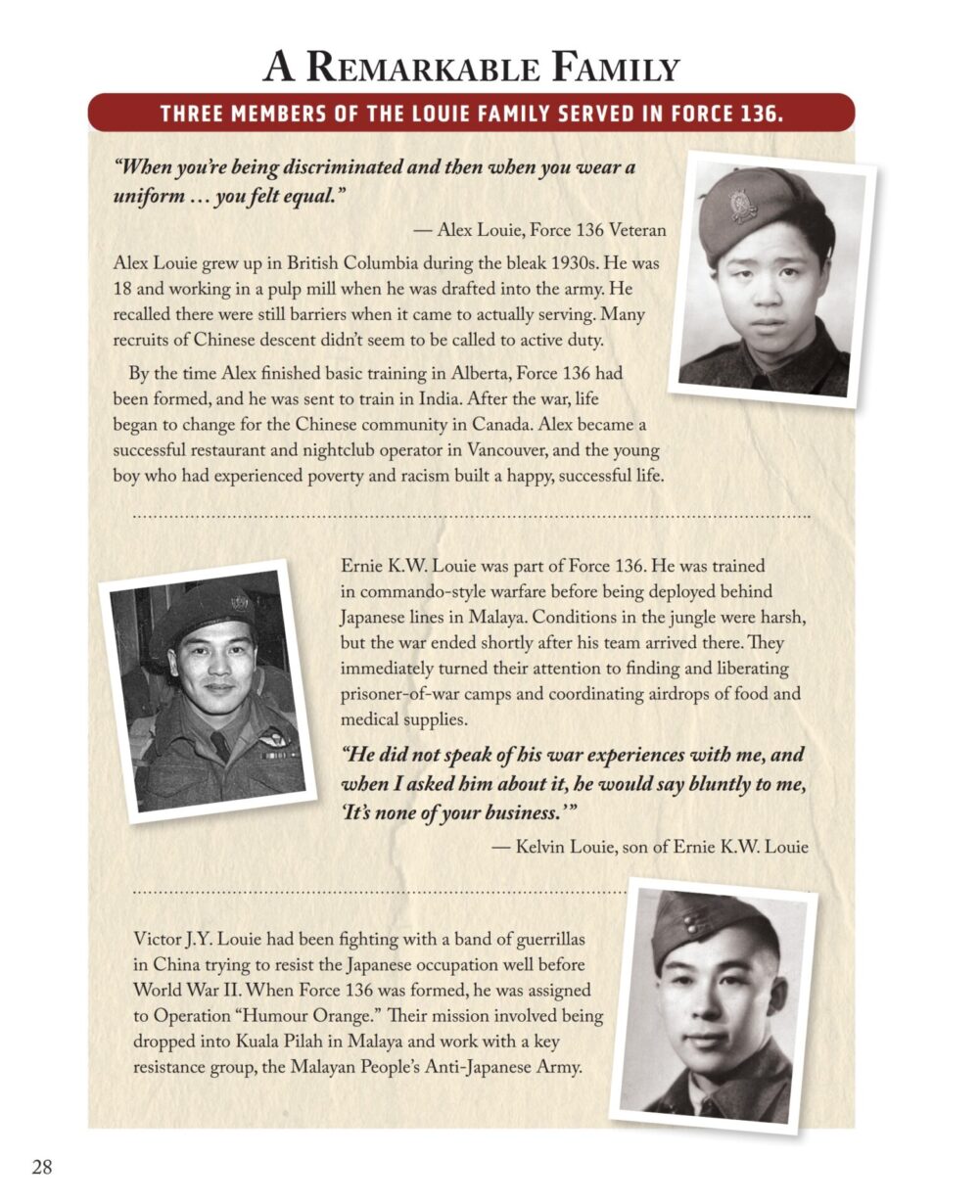

In my book, Endgame: The Secret Force 136, Alex learns about his Tai Gong’s (great grandfather’s) involvement in Force 136 while they play Xiangqi (Chinese Chess). In a nod to Ronald Lee’s story, the discovery is sparked by some precious photographs. While Tai Gong is a composite of the many men I read about, the historical notes at the end highlights a number of real veterans, including three from the same family. My hope is that this book will be used in many classrooms, so the Force 136 story becomes better known and recognized as an important part of Canadian history.

This blog was guest written for Honouring Bravery by author and educator Catherine Little. For more information on Catherine and her book, Endgame: the Secret Force 136, visit Plumleaf Press.

Sources:

Événements marquants de l’histoire des communautés asiatiques au Canada, Government of Canada

Force 136: Chinese-Canadian veteran reflects on service in special forces unit, CBC News

Force 136: Chinese Canadian Heroes

Fear, courage and cyanide pills: Chinese-Canadian veterans celebrated at Vancouver museum, Globe and Mail

Chinese Canadians of Force 136, Canadian Encyclopedia

Past Presence: For genealogists and family historians

Feature image: cover of Endgame: The Secret Force 136. Image reproduced with permission by Plumleaf Press.