Few people have the distinction of being called a legend in their lifetime. Stewart East was one of these remarkable individuals.

Becoming a Padre

Stewart Bland East was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba on April 29,1908. As a young man, his classmates described him as always having a smile for everyone. In 1935, he became an ordained minister and worked as a travelling preacher, or “circuit rider” in Saskatchewan. In 1938 Stewart married Mary Richardson and the two settled in Jarvis, Ontario.

Stewart joined the Canadian Chaplain Services in July 1940. Standing at 6’ 6’’ tall, Stewart was likely the tallest “padre” in the active service. He was posted with the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry and later transferred to the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. On October 28, 1942, he was again transferred to the 48th Highlanders and stayed with the regiment through most of the Italian Campaign.

During the war, a military chaplain’s role was to provide “spiritual and moral welfare” to the soldiers. However, Stewart always went above the call of duty. The soldiers were “his men”, regardless of their religious affiliation. For the members of the 48th Highlanders, Stewart East was more than a chaplain: he was a friend.

As a military chaplain Stewart duties included:

- Fostering religious, spiritual and moral well-being

- Offering a ministry of presence in a multitude of environments (at home and abroad)

- Participating in the life of the worshipping community

- Officiating at special functions

- Advising the commanding officer regarding the spiritual and ethical well-being and morale of their unit

Operation Husky

On July 10, 1943, the 48th Highlanders landed in Sicily as part of Operation Husky (the codename for the allied invasion of Sicily). The Sicilian summer was in full force and on July 12th, the heat became unbearable. The land was dry and dusty, and some men were collapsing from heat exhaustion. The soldiers desperately needed water. Seeing an opportunity to help, Stewart acquired six bottles of water from the quartermaster during the march and worked to ensure that the troops stayed hydrated. He continued acting as a supplementary water supply throughout the Italian Campaign.

Unlike most chaplains, who worked from the rear headquarters, Stewart began insisting that he sleep with the Medical Officer at the Regimental Aid Post, which was on the front lines close to the soldiers. Stewart became excellent at administering first aid and began to help the medics with some of their work. Many members of the 48th assumed that this was part of the job of a chaplain, but Stewart was, in fact, going beyond what was necessary of him in his role.

Ortona

By Christmas 1943, The 48th Highlanders had already reached Central Italy and were near Ortona in the Province of Abruzzo. They had been tasked to seize the high ground between San Tomasso and Ortona to prevent Germain troops from escaping Ortona. In what was known later known as “the Daring Gamble” the 48th Highlanders snuck single file into German territory via a footpath in the middle of the night. Through some miracle, the entire battalion reached their objective over a kilometer into German territory. However, the 48th Highlanders were surrounded by German troops. By Christmas, they had begun to run low on supplies, the batteries for their wireless sets were dying, and stretcher bearers were needed. A party of reinforcements from the Saskatchewan Light Infantry were to be brought up the footpath by Captain George Beal. Stewart was to be at the rear of the party to help get the men to the battalion safely. As they climbed the path, the group became separated. In the dark, Stewart rounded up the 60 separated men and guided them up the path.

Within minutes of arriving, Stewart was already checking in on the men of the 48th Highlanders, which helped reassure them that “everything was all right now”. With the additional supplies, and some later tank reinforcements, the 48th Highlanders were able to continue fighting until the German troops retreated. Stewart buried the dead (from both sides of the conflict) on the high ground where they fought and called the area Cemetery Hill. This name stuck and the battle was later known as the Battle of Cemetery Hill.

On December 31st, the 48th Highlanders captured the city of San Tommaso. Stewart decided that he would create a forward regimental aid post in the town, as the medical officer was busy tending to casualties elsewhere. He often was out collecting injured soldiers himself with the stretcher bearers.

“I was so surprised to discover that tall 48th officer was a Padre- you could have knocked me over with an olive,” said a Saskatchewan Light Infantry corporal. “He stopped being nice and stormed at us like a sergeant-major.”

– Dileas: A History of the 48th Highlanders

Taking care of the fallen

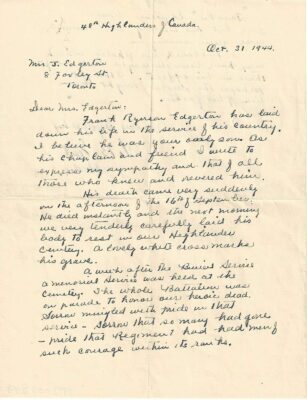

One of the unpleasant jobs that Stewart dealt with throughout the war was the retrieval and burial of soldiers who died in battle. Often, under the cloak of night, Stewart would take small groups of stretcher bearers and retrieve the fallen. This was often a dangerous task, but Stewart felt that it was his duty to ensure the fallen received proper burials. Stewart would often dig the graves himself. He cared deeply for these men, even in death. By the end of the Italian Campaign, Stewart had made sure that every 48th Highlander was accounted for, even if other chaplains had buried them. He also wrote notes to the family of the fallen. This sense of duty did not just extend to members of his regiment. On March 4, 1944, the 48th Highlanders relieved the Royal Canadian Regiment after they’d been involved in a brutal attack. That night Stewart led retrieval parties to collect as many fallen soldiers as he could. By the end of the night, they had collected 11 men.

In May 1944, Stewart and the other members of the 48th Highlanders made their way up the Liri Valley. While on patrol, he and a stretcher bearer found themselves in enemy territory. While there, they came across the body of a soldier from the Royal Canadian Regiment. Knowing that the body would have been moved if it was not for the fact that it was behind enemy lines, Stewart and the stretcher bearer retrieved the body so that they could give the soldier a proper burial.

The Hitler Line and beyond

The 48th continued through the Liri Valley towards The Hitler Line. The Hitler Line was a heavily armed series of German defenses that prevented allied forces from moving north towards Rome. On May 22nd, the 48th Highlanders attacked the Hitler Line. During the battle, Stewart began creating a casualty collecting post, all while German troops fired mortars and shells towards him. Stewart was hit in the arm but continued to help. Shortly after, he was wounded again, this time in the leg. He quickly tended to his wound by himself and applied a tourniquet. Stewart knew that he would have to leave the fight, but before he did, he found a stick to help support him and visited each of the company’s positions, in order to reassure the soldiers that everything would be alright. After recovering, he was allowed to rejoin the 48th Highlanders.

However, as the war raged on, its toll impacted Stewart more and more. “‘I was all right if I did not have to bury more than three,’ said [Stewart]. ‘When there were more to be found, and then searched for their personal things, and then buried, I was upset.’” Stewart put his whole heart into his work, sometimes to the detriment of his own well-being. For example, according to one account, he once stayed up for 72 hours straight helping the troops. In January 1945 Stewart became ill and he was ordered back to England.

Stewart’s actions during the war did not go unnoticed. For his bravery at the Hitler Line, Stewart was awarded the Military Cross. He was subsequently made a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for his service throughout the Italian campaign. He received both from the King at a ceremony at Buckingham Palace on May 18, 1945. The 48th Highlanders never forgot Stewart’s bravery and compassion, and continue to proudly celebrate the aid and support that Stewart provided them during the war.

Post war

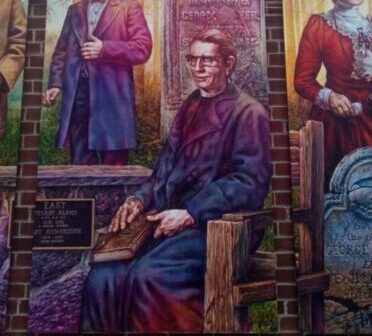

After returning from the war, Stewart returned to working as a minister. By 1947, he was working as the minister of Islington united Church in Etobicoke and helped organize the construction of their new church. He continued to work at the church until his retirement in 1973.

Stewart continued to be an active member of the local community in his later life. After leaving the church, he was elected as city alderman in Etobicoke’s Ward 2 and held the position until 1980. In 1980, he spearheaded the campaign to save Applewood Shaver House, birthplace of politician J.S. Woodsworth, from being demolished. He also acted as the chaplain of the Warriors Day Parade Council for many years. For his contributions to his community, Stewart was awarded the Jean Hibbert Memorial Award by the Etobicoke Historical Society in 1982 and was inducted into the Etobicoke Hall of Fame in 1988. Stewart passed away in 1995 at the age of 87. He left behind a rich legacy of community service and dedication to others.

Article written by Anthony Badame for Honouring Bravery.

Sources

Aitchison, Don “Padre Stewart East Legendary 48th Regimental Chaplain in WWII” The Falcon Yearbook 2015:38-40.

Beattie, Kim. Dileas: A History of the 48th Highlanders.

Cormack, R.L. “ The Rev. (Padre) Dr. S.B. East” The Falcon 24(1): 3-4.

Mural Map, Village of Islington.

Rev H/Major Stewart Bland East, MBE, MC , 48th Highlanders of Canada Museum.