Learning goals

In this learning activity, we are learning to:

- recognize and discuss the contributions of veterans and members of the Canadian Armed Forces who have made positive impacts on Canadian society

- develop an understanding of the challenges that these individuals overcame within both the military and Canadian society

- reflect on the meaning of resilience and on how members of the Canadian Armed Forces have exemplified it both on and off the battlefield

Remembrance Day

Every year on November 11, we take time to remember the service and sacrifice of veterans and current members of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF). We honour the individuals, who sacrificed comfort for hardship to ensure war did not reach Canadian soil. Today, they continue to maintain peace and security for all Canadians.

To serve in the Armed Forces is to prepare for hardship and to be willing to sacrifice your own personal freedoms, from time with your family to the ultimate sacrifice: your life. That resilience in the face of danger and that sense of sacrifice often helps build great leaders. In this module, we will explore stories of veterans who were leaders in their communities and who continued to fight for a better Canada after their years of service.

The CAF over the years

While the focus of this module is to bring to light the contributions that CAF members have made to Canada off the battlefield, we must also remember the sacrifices that countless other CAF members have made in service to their country. The Canadian Armed Forces have played an important role in past international conflicts and on the ground during disasters in Canada, often at great cost.

Press the following external link to learn more.

A timeline of the Canadian Armed Forces

Reflect on the following quote about the service and sacrifice of the Canadian Armed Forces.

On this Remembrance Day, I’m feeling grateful. The sacrifice and service of those in the Canadian Armed Forces has made our way of life possible.

– Naheed Nenshi, former Mayor of Calgary

Discussion

What do you think Nenshi means when he says, “The sacrifice and service of those in the Canadian Armed Forces has made our way of life possible”?

You may use the following tips to guide your discussion. Be mindful of appropriate discussion etiquette and be respectful of your classroom community.

Press the Show Tips button to learn more.

Show Tips

Join in – Discussions are shared learning spaces. It’s true that the more you participate, the more you will gain in your learning journey.

In support of inclusion – Everyone’s opinions and thoughts count. Be respectful of others when you share your thinking or respond to the thinking of others. Be open to changing your mind and considering new and different ways of understanding.

Use examples from the learning activity – Depending on the discussion topic, it’s always a good idea to relate what you are learning and sharing to the experiences you have had in the learning activity. It’s a great way to reinforce your learning.

Think before you share – Consider the value, relevance, and tone of your shared ideas, so that it is appropriate for everyone in your class, including your teacher.

Resilience

Members of the Canadian Armed Forces have shown great resilienceThe capacity to withstand or to recover from difficulties. on the battlefield. Through their determination and service to their country, they fought to ensure a safe and free Canada. After successful military careers, some veterans continued to show resilience and determination in civilianA person not currently in the Armed Forces. life, doing remarkable things to help Canadians.

Journal

Can you think of a time when you, or someone you know, overcame a difficulty through resilience?

Some examples might include:

- dealing with someone who hurt your feelings

- achieving something you, or others thought you couldn’t

- overcoming a failure, for example, failing a class and attending summer school

Record your thoughts in a method of your choice. You may use the Journal Reflection Prompts to complete the activity.

In the “Minds On” section, we discussed the service and sacrifice of the Canadian Armed Forces and reflected on resilience. We will now explore some of the ways veterans and Canadian Armed Forces members have positively impacted Canada.

Think

What liberties and freedoms do Canadians have today, compared to 75 years ago?

Social impacts of conflict

Members of the Canadian Armed Forces have been at the forefront of many advancements in Canadian society. Although initially intended for the military, much of the resulting research and progress found positive applications in everyday life.

Press the following tabs to learn more.

The need to prevent deaths and illnesses related to war has led to many advancements in medicine. Born in Bowmanville, Ontario, Group Captain Albert Ross Tilley worked at the Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead during World War II. He primarily treated members of the Air Force who were severely burned as a result of their planes being shot down. Through his work, he pioneered new methods to treat burn victims, including using special bandages and saline baths. When he returned to Canada, he created Canada’s first adult burn treatment centre in Toronto.

Many Canadian inventors have created important technological innovations while working on projects for the military. One such invention was the walkie-talkie, invented by Donald Hings. Although Hings first created an early walkie-talkie (then known as the packset) in 1937, he substantially improved the technology while working for the Canadian government during World War II. It is important to remember that cell phones had not yet been invented, and the walkie-talkie provided reliable wireless communication. Around 18,000 walkie-talkies were created in Toronto, Ontario during the war. Hings was made an honourary member of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals and the technology he created is still important in telecommunications today.

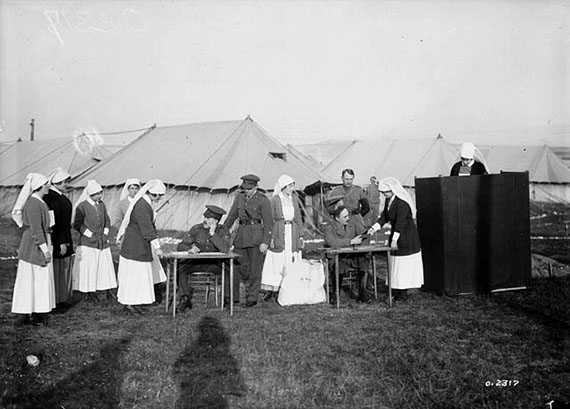

Unlike other allied nations in World War I, Canada was the only country where military nurses were fully enlisted officers in the Armed Forces. Canadian nurses were granted the rank of Nursing Sister, which was equivalent to a Lieutenant, and earned $2.00 a day. This amount was double that of a Private in the trenches and was up to four times the average daily salary of a typical nurse in some Canadian cities. In 1917, Nursing Sisters were also the first women to receive the right to vote in federal elections and paved the way for other women in Canada to receive the vote.A condition that affects individuals who have gone through or witnessed traumatic experiences. Common symptoms include problems sleeping, agitation, anxiety, and depression.

We have explored how members of the Canadian Armed Forces contributed to advancements in Canadian society. Their efforts have found positive applications in everyday life. We will now explore how trailblazers and changemakers also fought for change in the military.

Military reform

Just like Canadian society, the Canadian Armed Forces have not always been as inclusive as they are today.

Over the years, numerous individuals hoping to serve their country faced discriminatory government policies that prevented or outright barred them from military service. It took the courage of several extraordinary individuals to challenge these policies and ensure that military service was open to all.

Discussion

Why is it important to have diversity and equality in the Canadian Armed Forces?

Press the following tabs to learn about extraordinary individuals who fought for military reform. You may use the Learning Log to record the significance of these trailblazers and changemakers.

When World War I broke out in 1914, Canadians across the country rushed to enlist. In December of 1915, Jacob Courtney, a young Black man from Owen Sound, Ontario, volunteered to serve and fought overseas in a predominately white battalion. He witnessed heavy fighting in the Battle of Canal du Nord, France, which was part of the military offensive by the Allies that ended the war in 1918. He was awarded a Good Conduct Badge for his service.

In 1917, the Canadian government passed the Military Service Act which forced all able-bodied men aged 20-45 to enlist in what is known as forced conscription. Neither the Canadian Military nor the Government of Canada had a policy that excluded Black Canadians from joining the military. In fact, the government did not register the ethnicity of anyone who enlisted on their service records. However, Black Canadians faced barriers to enlisting in the military and faced racist attitudes when trying to enlist. In some cases, local recruitment officers did not accept Black Canadians’ applications to serve in the Canadian Army. Jacob Courtney inspired his younger brother Henry to enlist, but Henry could not find a battalion that was willing to take him.

Determined to serve Canada, Black Canadians across the country began to pressure the government to allow more Black Canadians into the military. Henry Courtney wrote letters to the editor of the Canadian Observer newspaper. He writes: “I still want to do my bit”, said Henry, “I am well and hearty and strong. Never have I been sick”. Letters like Henry’s helped persuade the military to accept more Black Canadians into service. Although the British War Office refused to allow any Black units into combat, a solution was proposed: the creation of a labour battalion. On July 5, 1916, the Department of Defence and Militia authorized the No. 2 Construction Battalion, an all-Black labour battalion.

Henry Courtney quickly took the opportunity to join the war effort and enlisted with the battalion on August 30, 1916. While overseas, he and the battalion assisted the Canadian Forestry Corps in construction-related projects and created invaluable infrastructure for the war effort. The role of the No. 2 Construction Battalion was critical as they were responsible for maintaining the roads which allowed supplies to move between army camps. They also managed the water supply and were responsible for all the timber, essential for trenches, bridges and observation posts in the war.

Jacob and Henry Courtney were determined and courageous. Black communities across the country demonstrated their dedication to Canada through their service in WWI. Around 1,300 Black Canadians enrolled in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). These men showed bravery and resilience during a time of challenge for all Canadians.

Michelle Douglas joined the Canadian Armed Forces in 1986, after studying law in university. She excelled in her military training and was invited to join an elite military police branch: the Special Investigations Unit (SIU). The SIU investigated the most serious crimes in the military, which at the time included investigating allegations of homosexuality.

During the Cold War (1947-1991), the Canadian government became concerned with the possibility that gay people in the military, RCMP, and civil service could pose a security threat. During that time period, many people kept their sexuality secret to avoid persecution. This led government officials to believe they could be blackmailed into revealing classified information.

While Michelle Douglas was working for the SIU, the unit received allegations against her in regard to her sexuality. Despite being interrogated and asked to take a polygraph test, she refused to admit to the accusations or to be pressured into naming other members of the Armed Forces who were gay. She returned to her unit and persevered despite colleagues and supervisors who would not speak to her or assign her work. Though she denied the allegations at first, Douglas eventually made the decision to come out, despite knowing that it would end her military career. She was discharged from the military in 1989 for the reason of being “not advantageously employable due to homosexuality”.

In 1990, Douglas sued the Canadian government over her treatment, turning her experience into an opportunity for positive change. As a result of her lawsuit, the Canadian Armed Forces formally changed their policy against homosexuality in 1992, two years before the Supreme Court officially listed sexual orientation as a protected right under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. For more than 30 years, Douglas has continued to champion the rights of 2SLGBTQI+Acronyms like 2SLGBTQI+ would not have been used at the time. Instead, terms such as “homosexual” would have been more common. The acronym 2SLGBTQI+ is used here because it encapsulates a broad spectrum of identities and experiences. Applying such terms retrospectively helps us to better understand and acknowledge the diversity of identities that existed historically, even if they were not labeled as such at the time. Canadians. In 2023, the Canadian Armed Forces appointed her as military Honorary Colonel of the Chief Professional Conduct and Culture organization. Douglas proudly serves Canada in this new role and believes it as an important act of reconciliation to acknowledge the contributions of all Canadians.

Michelle Douglas’ actions show courage, integrity and selflessness. At a time when many individuals lived in fear of having their sexuality discovered, she came out publicly to her family, her employers, and all Canadians.

When people come together it is an unstoppable force. Form groups with others that are like-minded and advance your mission, advance your purpose. Do not be deterred by time or money.

– Michelle Douglas

During World War I, thousands of Indigenous men wanted to serve in the Canadian Expeditionary Force and travelled hundreds of kilometers to reach recruitment offices. Over 4,000 Status First Nations soldiers served in World War I. Thousands more Inuit, Métis and non-Status soldiers also enlisted, but their Indigenous identities were not always recorded. Many First Nations soldiers became highly respected amongst military personnel, including Oliver Milton Martin.

Born in 1893 on the Six Nations Grand River Reserve, Oliver Milton Martin was a member of the Kanyen’kehà:ka (Mohawk) Nation. In 1909, he joined The Dufferin and Haldimand Rifles of Canada and enlisted for World War I in 1916. He was reassigned to the 107th Timberwolf Battalion and fought with the battalion in France and Belgium. In 1917, after surviving a German gas attack, Martin transferred to the Royal Flying Corps. He trained as an observer in England, and, in June 1918, he became one of only a few Indigenous pilots who fought in WWI.

Although some First Nations soldiers felt that they were treated with respect on the battlefield by other soldiers, there were still cases of discrimination. When Martin was a lieutenant, he was assigned to transport 400 Indigenous soldiers to a military camp. Their train had a four-hour layover in London. Senior officers told Martin that he was not allowed to let any of them off the platform as they believed that as Indigenous peoples, the soldiers would end up causing some sort of disturbance in town. Martin ignored the senior officer and allowed the soldiers to leave the station. Every soldier was back on time to leave, and no disturbances occurred.

Martin returned to Canada in 1919, became a teacher and continued to serve as Lieutenant Colonel of The Dufferin and Haldimand Rifles of Canada. He served Canada on the home front in WWII as a colonel of the 13th Infantry Brigade, became the first Indigenous person to hold the role of brigadier in 1941, commanded the 18th Infantry Brigade in Nanaimo, BC and was in command of troops in Military District 2 in Ontario. He retired from the military in 1944. After the war, he became the first Indigenous person to receive a judicial posting in Ontario and became an advocate for education and Indigenous rights. He testified at the 1946 Special Joint Committee on revising the Indian Act and was inducted into the Indian Hall of Fame. The Royal Canadian Branch No. 345 in East York was named in his honour: the Brigadier O.M. Martin Branch.

Oliver Martin demonstrated his dedication to serve Canada throughout his military career despite the challenges as an Indigenous person. He selflessly risked his own commission to ensure his soldiers had the same rights as non-Indigenous soldiers and taught recruits with kindness.A condition that affects individuals who have gone through or witnessed traumatic experiences. Common symptoms include problems sleeping, agitation, anxiety, and depression.

Complete the following self-check question to determine what you may now know about the Status First Nations soldiers who fought during World War I.

Zero-tolerance policy

The Canadian Armed Forces now has a zero-tolerance policy for discrimination and harassment. Members are expected to uphold the values of respect, dignity, and equality.

You may press the following external links to learn more.

Website of the Canadian Armed Forces (Opens in a new tab)

Website of the Government of Canada: National Defence section

A more inclusive Canada

Veterans and members of the Canadian Armed Forces not only helped to make the military more inclusive, but some also tackled larger issues of racism, discrimination and injustice within Canadian society after their years of military service. Those who served overseas often risked their lives for their fellow citizens and yet, when they returned home to Canada, were met with the same discriminatory legislation as when they left. For a number of extraordinary veterans, their experiences in the military contributed to them becoming active members of social movements, and lobbying the government to enact legislative changes.

Press the following tabs to learn more. You may access the Learning Log to record the significance of these trailblazers and changemakers.

Chief Francis Pegahmagabow was one of the most decorated Indigenous veterans of World War I. He was born in Shawanaga First Nation, an Anishinaabe community near Nobel, Ontario. He enlisted in 1914 at the age of 23 and arrived in France in February 1915. He was one of over 4,000 Indigenous soldiers to volunteer to fight for Canada in WWI. During the war, he became the most effective sniper of the Canadian Expeditionary Force and captured over 300 German prisoners. He fought in the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915, the Battle of Mont Sorrel in 1916, the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917, Amiens and the Second Battle of Arras in 1918. On multiple occasions, he went behind enemy lines to gather vital intelligence.

During the Battle of the Scarpe, Pegahmagabow’s company was almost surrounded and nearly out of ammunition. He travelled through machine gun fire and risked his life to secure ammunition for his company to defend themselves against the attack. His actions garnered respect, and he received the Military Medal with two bars. This was an exceptional recognition of his service and accomplishments as only 38 other Canadians received two bars. He received the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. He is one of the most highly decorated Indigenous soldiers in Canadian military history.

After the war, he settled in the Parry Island Reserve (now called Wasauksing First Nation) near Parry Sound, Ontario. In 1919, he tried to apply for a loan through the Soldier’s Settlement ActAn advantageous loan program to help veterans purchase land, stock and materials for farming., but the local denied Indian agentIndian agents oversaw the implementation of the Indian Act, which attempted to assimilate First Nations Peoples and impede their sovereignty on reserves. his claim. At this time, when many Indigenous soldiers returned from war, they lost their Indian Status because they had been away from their reserve land for so long. This was unfair to the Indigenous soldiers who volunteered to fight in the war. Pegahmagabow decided to take action and ran for councillor in his community. He was eventually elected chief in 1921. As chief, he pushed for his nation’s right to self-determination and often challenged the local Indian agents. Throughout the 1940s, he joined other Indigenous leaders to protest the government’s treatment of Indigenous Peoples of Canada. He fought against the ability of the government to enfranchiseEnfranchisement is a legal process for terminating a person’s Indian status. Note: The term ‘Indian’ is not used anymore. a First Nations person and have their Status relinquished without their consent.

In 1945, he joined the National Indian Government, an Indigenous organization that lobbied for Indigenous self-government, and was elected Supreme Chief of the organization in 1949. Although Pegahmagabow died in 1952, he lived long enough to see the Indian Act amended in 1951, which put a stop to compulsory enfranchisement of First Nations individuals and removed the ban on the Potlatch, Sundances, and other First Nations ceremonies.

Pegahmagabow’s medals are on display at the Canadian War Museum and are a testament to his bravery and extraordinary military achievements. Through numerous leadership roles during his career with the military and afterwards, he fought to better the lives of Indigenous Canadians. He demonstrated great determination, empathy and resilience.

Wee Hong (Walter) Louie was born in Shuswap, British Columbia in 1894. Although he was born in Canada, children of Chinese immigrants were not granted citizenship at birth. Individuals of Chinese descent living in Canada were not eligible for Canadian citizenship and could not vote in elections until 1948. Despite this, Louie chose to fight for Canada in World War I and enlisted in Kamloops on April 9, 1917. However, his brother, Wee Tan, was rejected for being Chinese. Refusing to accept this, Wee Tan travelled for three months to Calgary where he was able to find a battalion that accepted him. The brothers were part of a group of 300 Chinese Canadians who served Canada during WWI.

Louie first trained to be a gunner, went to France with the 29th Battalion and cheated death more than once. During the Battle of Arras in France, German troops severely attacked the battalion using gas and artillery. Luckily, Louie survived. Later, in August 1918, his battalion crossed over a kilometer of open ground in broad daylight while under intense fire in order to capture a railroad near the village of Rosières, France. By the end of the war, Louie had transitioned to working as a driver and wireless communications, where he learned the basics of radio repair.

After returning from the war, he studied electrical engineering at university and moved to Orillia, Ontario, where he purchased a store to sell and repair radios. He was unable to get a business license due to his Chinese heritage. Determined to open his business, he sent a letter to Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King along with his uniforms and medals. In the letter, he said he was returning the medals and uniforms as a sign of protest. He was born in Canada, fought for Canada, and yet, as a Chinese Canadian he could not get a license to start his own business. In response, King returned Louie’s belongings with an apology. The business license was subsequently granted. Louie ran his business, West End Radio, until he retired in 1976.

Walter Louie’s story demonstrates his deep tenacity and willingness to serve Canada. He was determined to fight for Canada and open his business which showed his ability to overcome obstacles that are testament to his determination.

Although anti-Asian sentiment was not new to Canada, World War II brought about a significant increase in anti-Japanese policy from the Canadian government. On December 7, Japanese forces bombed Pearl Harbour and Canada officially declared war on Japan. Under the War Measures Act, all people of Japanese origin, regardless of citizenship, became enemy aliens and had to register with the government. By February 1942, Prime Minister Mackenzie King ordered the forced removal of all individuals of Japanese heritage from the Canadian Pacific coast. Approximately 22,000 Japanese Canadians were affected.

Frank Moritsugu was 19 when he and his family were forced to leave their home in Vancouver and move to internment camps. They could not bring much with them and most of the possessions that they left behind were vandalized or stolen. Moritsugu’s family was separated and sent to three different internment camps. Under the rules of their internment, Japanese Canadians could leave the internment camps if they left British Columbia and went to a province in the east. After two years of being separated, Moritsugu reunited with his family in St. Thomas, Ontario, where his family relocated to work on a farm.

However, as the war with Japan continued, there became a need for members of the Armed Forces who spoke Japanese to work as interpreters for Japanese Prisoners of War. Frank Moritsugu, a Japanese Canadian, wanted to fight for Canada and voluntarily enlisted in 1945 with the Intelligence Corps of the Canadian Army. His parents were unhappy, but he convinced them that by enlisting, he was showing other Canadians that Japanese Canadians were just as patriotic as everyone else and should be seen as equals. During his service, Moritsugu worked in intelligence operations alongside British troops in India and Sri Lanka. Part of his duties included teaching Japanese to troops and acting as a translator.

Although the war ended in 1945, government policies that restricted the movement of Japanese Canadians lasted until 1949 and it was no different for Japanese Canadian veterans. When Moritsugu came back from the war in 1946, he was obligated to carry an RCMP registration card. He was upset and took action, writing about the incident in a Japanese Canadian newspaper to show how ridiculous the policy was.

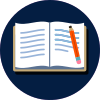

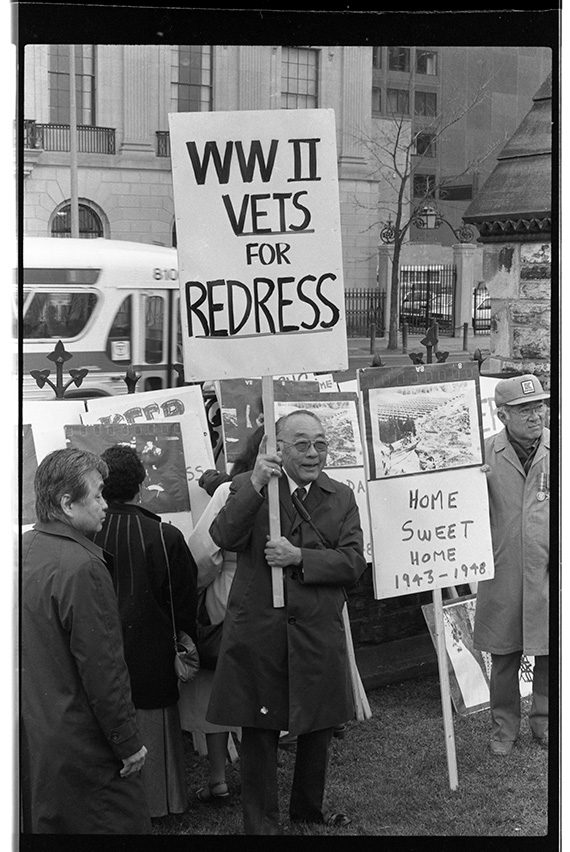

During the 1980s, Japanese Canadians fought the government for recognition of the poor treatment of Japanese Canadians during World War II. As a veteran who had worked hard to show his loyalty to Canada, Moritsugu wanted to help in this fight. He was a member of the National Association of Japanese Canadians’ Toronto chapter and helped circulate communications for the redress campaign team. In April 1988, he also attended the redress rally on Parliament Hill. After pressure from Japanese Canadians, the Canadian government formally apologized to Japanese Canadians on September 22, 1988, and provided compensation to those citizens affected by internment. The government also repealed the War Measures Act and replaced it with the Emergencies Act, which ensures that the government’s actions are subject to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Social welfare

A number of veterans have become the creators and leaders of organizations, such as unions and charities, that promote social welfareConcerned with the well-being of a society and aims to ensure that the needs of individuals are met..

Did you know?

The Canadian National Institute for the Blind and War Amps organizations were created by veterans.

The work of these organizations has also led to the creation of government policies that have helped improve the lives of Canadians around the country.

Press the following tabs to learn about the contributions of veterans to social welfare in Canada. You may use the Learning Log to record the significance of these trailblazers and changemakers.

In the early 20th century, there were few resources for people with physical disabilities. As more individuals returned wounded from World War I and World War II, new services were created to provide support. Although originally made to serve veterans, these organizations quickly expanded to help civilians as well.

John Gibbons Counsell was born in 1911 in Wentworth and went overseas with the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry. During the Dieppe Raid, he was wounded in the back, which resulted in permanent paralysis. At the time, spinal cord injuries were not well understood. Most doctors believed that not much could be done for individuals with spinal cord injuries and that they would remain “hopeless invalids”. Counsell became extremely depressed in hospital, but with support from his doctors and his peers, his outlook improved. Upon his arrival back in Canada, he began to advocate for injured veterans. Counsell believed in the importance of independence for disabled veterans and convinced the government to supply wounded members of the Armed Forces with foldable, self-propelling wheelchairs. Unlike traditional wheelchairs, these new chairs would allow better mobility and further help veterans reintegrate into society after being injured.

In January 1945, Counsell helped to open Lyndhurst Lodge, Canada’s first rehabilitation centre for spinal cord injuries. Originally opened to serve veterans, Lyndhurst Lodge transitioned to providing programs for civilians. Days after the opening of Lyndhurst Lodge, Counsell founded the Canadian Paraplegic Association (CPA), now known as Spinal Cord Injury Canada. The CPA aimed to help individuals with spinal cord injuries have active and independent lives. They also created training and peer support programs. In 1951, he helped found the National Advisory Committee on the Rehabilitation of Disabled Persons and helped create the groundwork for Canada’s current disability policies.

Stanley Grizzle was born in Toronto in 1918. As a young man, he worked as a railway porter, one of the few better paid employment opportunities available to Black Canadian men at the time. He established the Young Man’s Negro Association of Toronto in 1938 and thus began his lifelong fight to improve Black Canadian rights. In 1942, he received a notice of conscriptionThe drafting of people for mandatory military service. and trained in the Medical Corps in Newmarket, Ontario. While in England, Grizzle was put on latrine duty for refusing to become a batman, also known as a personal servant. Grizzle was reassigned to the quartermaster’s stores where he was in charge of delivering supplies and mail. He also performed orderly duties at clearing stations. By the end of the war, he was promoted to Corporal and went on to serve in France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany.

After WWII, Grizzle returned to his previous job in 1946 as a railway porter. Although they offered an important service on the railway, porters faced challenges. Railway porters could be dismissed without reason, were paid less than other non-Black railway workers and had to work long shifts, typically 72 hours with little opportunity for sleep. Grizzle, wanting to advocate for change, became the president of the Toronto chapter of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. The union successfully pushed for better wages and working conditions for its members.

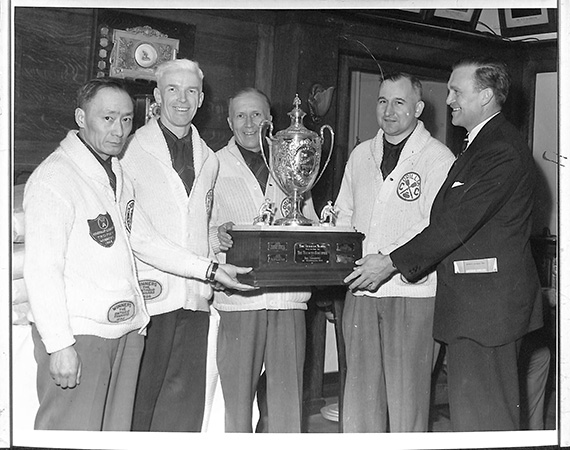

Grizzle continued his activism in the post-war years and was an influential member of the Joint Labour Committee for Racial Intolerance. The committee helped to enact Ontario’s Fair Employment Act in 1951, which made it illegal to refuse a person’s employment based on their race. In the 1960s, Grizzle became the first Black Canadian to be employed by the Ontario Ministry of Labour as a clerk with the Ontario Labour Relations Board. In 1978, he again made history as Canada’s first Black citizenship judge. Grizzle continued to work for labour and citizenship rights until his death in 2016.

Grizzle was proud of the work that he did in service to Canada. He showed resilience and a deep sense of justice both in the army and as a veteran who advocated for his community and country, helping enact significant positive change.

When I look back on the war, I thank God for the experience. It matured me. Because of my army-life experiences, I became a strong advocate of non-violent direct action in the settling of human differences.

– Stanley Grizzle

We have learned about inspiring trailblazers and changemakers who have made major contributions towards a more fair and inclusive Canadian society. Through their stories, we have explored significant changes made throughout Canada’s history.

Try it

Complete the following self-check quiz to determine what you now know about the contributions of trailblazers and changemakers from the Canadian Armed Forces.

Try the following questions and select the correct answer, then press Check to see how you did.

In this learning activity, we explored:

- the meaning of resilience

- the challenges members of the Canadian Armed Forces faced within both the military and Canadian society

- positive impacts made by members of the Canadian Armed Forces

We will now discuss how our understanding of trailblazers and changemakers may have changed throughout this learning activity. You may use your Learning Log to help guide your discussion.

Discussion

- What makes someone a trailblazer or changemaker?

- What qualities do they possess?

- Do all changemakers approach challenges in the same way?

After your discussion, you may want to discover more about some of the trailblazers and changemakers from the Canadian Armed Forces.

Discover more

Research a past or present trailblazer from the Canadian Armed Forces and record your research in a method of your choice.

You may choose to include:

- background information

- historical significance

- how they changed the Canadian Armed Forces or Canada for the better

- how their time in the Canadian Armed Forces shaped their desire to make change

You may choose to research a trailblazer from the following list:

- Adelaide Helen Grant Sinclair

- Albert Ross Tilley

- Bert Sutcliffe

- Buckam Singh

- Cliff Chadderton

- Colonel Sidney Lambert

- Edith Monture

- Elizabeth Smellie

- Ellanore Parker and Murnie Pugh

- Gerald (Gerry) Bell

- Gerald Gladstone Parris

- Harry Botterell

- Jean Suey Zee Lee

- Karen Hermiston

- Lawrence Bruce Robertson

- Leonard Braithwaite

- Onondeyoh (Frederick Ogilvie Loft)

- Roger Sacho Obata

- Roy Mah

- Seldon Thomas Parris

- Trooper Minoru Tanaka

- William Andrew White

Explore a world conflict, told through an interview with a veteran.

Choose one of the following videos to watch, and answer the corresponding questions in a method of your choice:

NOTE: The content in the following videos may be distressing for some of our viewers. The videos deal with sensitive subject matter, including examples of violence in war. Viewer discretion is advised.

Option 1: Interview with Veteran Romey Daley

The Korean War took place between 1950-1953. It is sometimes referred to as “the forgotten war”, as it was overshadowed by World War II, and fewer Canadians served in Korea than in previous wars. However, when North Korean troops invaded South Korea in 1950, more than 26,000 Canadians heroically volunteered to serve in this conflict.

Romey Daley was one of the brave veterans who volunteered to serve. In the following video, Daley shares his experience in the war, including the difficulties of life at the front, and on returning home. He says: “It is not a forgotten war. It is a forgotten victory.”

Watch the following video and answer the corresponding questions.

- Remember: What does the video “The Forgotten War: Korea” teach us about The Korean War?

- Understand: What do you think Romey Daley means by saying: “It is not a forgotten war. It is a forgotten victory”?

- Apply: The Volunteer Service Medal in Korea was introduced in 1991. What impact does this recognition have on veterans, and Canadians in general? What are some ways Canadians can recognize the service and sacrifice of veterans?

- Analyze: Why do you think is it important for veterans like Romey Daley to share their stories?

- Evaluate: Is Romey Daley a trailblazer and/or changemaker? Why or why not? Use evidence or examples from the video to support your answer.

- Create: Consider 3 questions you think are important to ask a veteran about their experience. Record these questions in a method of your choice.

Option 2: Interview with Veteran Sandra Perron

In 1989, following a Canadian Human Right Tribunal Ruling, the Canadian Forces permitted women in combat. Sandra Perron became the first female infantry officer in Canada and was a captain in the Canadian Forces. She completed two tours in former Yugoslavia, during a time of war and civil unrest. She faced great difficulty as a woman in the military, but persevered, eventually commanding 42 men while deployed in Croatia.

Watch the following video and answer the corresponding questions.

- Remember: What does the video “The Forgotten War: Balkans” teach us about The Balkan War?

- Understand: What do you think Sandra Perron means by saying: “I had debunked all their myths about women”?

- Apply: Sandra Perron created an organization called The Pepper Pod, which is based on a military maneuver, that aims to protect your buddy while you’re moving towards the enemy. How do you think organizations like The Pepper Pod support veterans? What other ways could we support veterans?

- Analyze: Why do you think it is important for veterans like Sandra Perron to share their stories?

- Evaluate: Is Sandra Perron a trailblazer and/or changemaker? Why or why not? Use examples from the video to support your answer.

- Create: Consider 3 questions you think are important to ask a veteran about their experience. Record these questions in a method of your choice.

Asset Acknowledgements

Some images supplied by Getty Images. Other images, graphs, diagrams, and illustrations in this course, unless otherwise specified, are TVO created.

12 airmen standing round Ross Tilley, Royal Canadian Air Force, International Bomb Command Centre Digital Archive, University of Lincoln, URL. Published n.d, accessed June 28, 2024. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 license (CC BY-NC 4.0).

Infantrymen of The Loyal Edmonton Regiment using a walkie-talkie radio during an advance, Ortona, Italy, 21 December 1943. Lieutenant Terry F. Rowe, Canada. Department of National Defense, Library and Archives Canada, URL. Published 21/12/1943, accessed June 28, 2024. PA-163932.

Nursing Sisters at a Canadian Hospital voting in the Canadian federal election, William Rider-Rider, Canada. Dept. of National Defence, Library and Archives Canada, URL. Published December 2017, accessed June 28, 2024. PA-002279.

Portrait of Jacob Courtney, “A” Company, 157th Battalion, CEF, unknown, Simcoe County Archives, URL. Published ca. 1916, accessed June 28, 2024. 2008-126.

Military portrait courtesy of Michelle Douglas.

Military image courtesy of Sandra Perron.

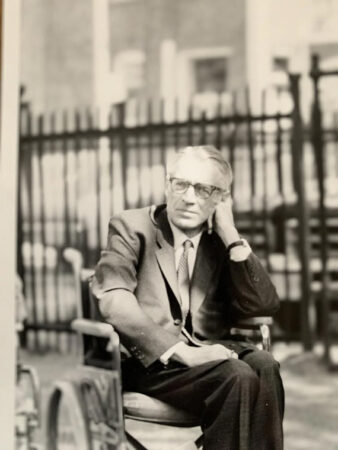

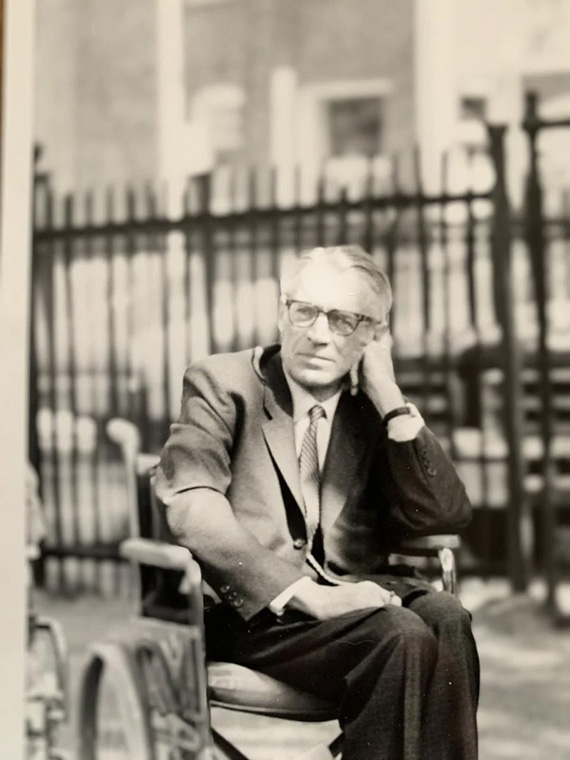

Brigadier Oliver M. Martin, Canada. Department of National Defence, Library and Archives Canada, URL. Published ca. 1943-1965, accessed June 28, 2024. eCopy.

Roger Obata with placard; Parliament Hill, Ottawa, Ontario. Gordon King, Nikkei National Museum, URL. Published 1988, accessed June 28, 2024.

Francis Pegahmagabow, Indiana University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Published 1962, accessed June 28, 2024. Used with permission. 1962-08-7679.

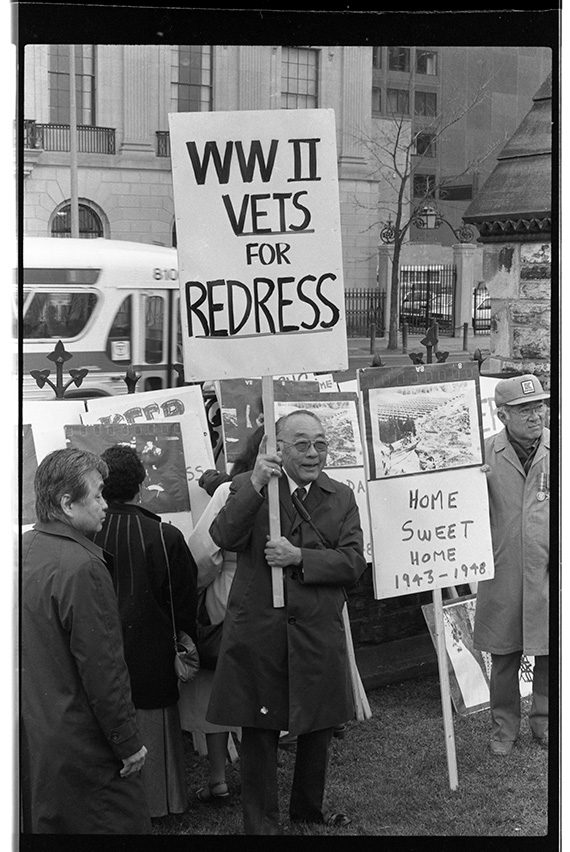

Wee Hong (Walter) Louie, Orillia Public Library. Accessed June 28, 2024. Used with permission.

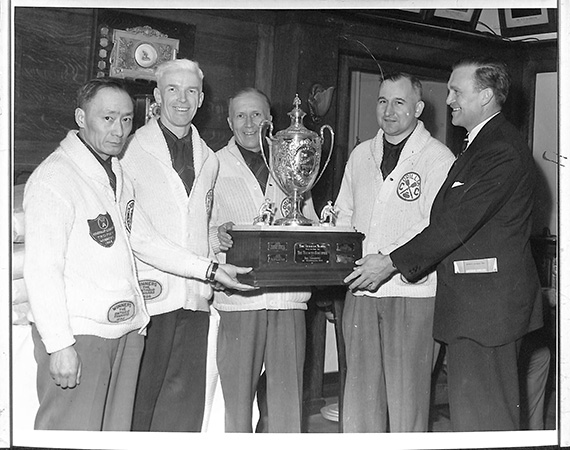

Frank Moritsugu, Andrew Danson, Library and Archives Canada, URL. Published 22/06/1989, accessed June 28, 2024.

John Gibbons Counsell, Spinal Cord Injury Canada. Published n.d, accessed June 28, 2024. Used with permission.

Veteran recognition, citizenship ceremony: St. Lawrence Hall, 157 King Street East (Stanley Grizzle portrait), Jose San Juan, City of Toronto, URL. Published 10/11/2005, accessed June 28, 2024. City of Toronto Archives Fonds 219, Series 2311, File 2074, Item 160.