On June 6th,1944, Operation Overlord, the largest sea-borne invasion in human history took place on the beaches of Normandy. The operation to open the western front of Europe took the form of an assault on the Nazis’ Atlantic Wall at five beaches: Gold, Juno, Sword, Omaha and Utah. Trooper Lorne A. Tozer was among the thousands of Canadians who came ashore on Juno that day. On the same day thousands of kilometres away, his younger brother, Elvin ‘Byng’ Tozer, made his way to Fredericton, NB and enlisted in the Canadian Army with four of his friends. United by this single day, these two brothers, my uncles, would experience very different wars.

The Third Wave

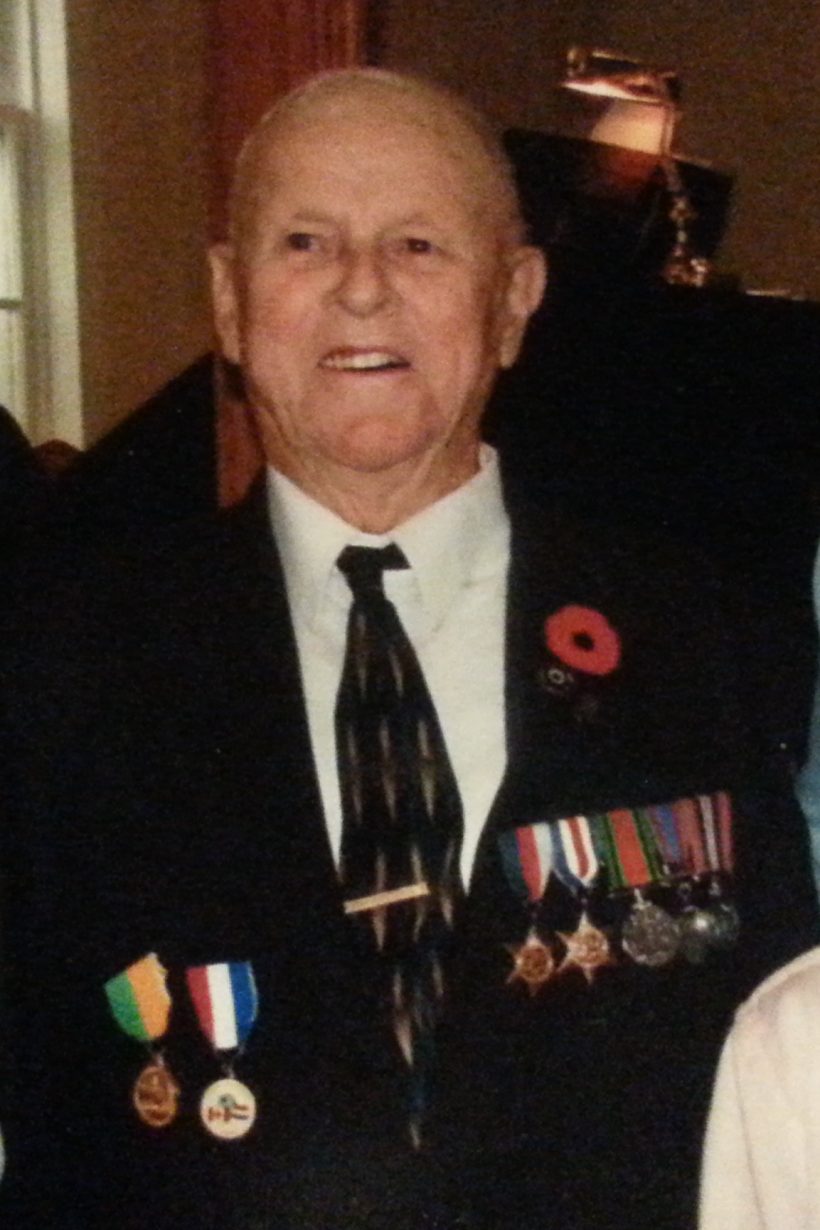

On November 26, 1942, Lorne and his friend, Hugh Mullin, made their way to Fredericton, NB and volunteered for active service. When asked why he had chosen to leave the Miramichi to join up, his response, like many, was, “there was nothing going on around here.” He was off on a great adventure. Lorne was the second son of Elvin and Hattie Tozer, and, at the time he enlisted, had eight living siblings. After completing ‘Wheel and Track’ training at Camp Borden, he was sent to England on June 27, 1943, aboard the SS Andres. Originally part of the Halifax Rifles, this unit was broken up and Lorne would serve with the Sherbrooke Fusiliers throughout the war.

On June 3rd, 1944, in Bournemount, England, Tozer backed his recently waterproofed three-tonne GMC-built Canadian Military Pattern (CMP) fuel truck onto the assigned Landing Craft Tank Mark IV (LCT4) in preparation for Overlord. The gasoline was not carried in a single large tank but was in stackable reusable metal jerry cans. He had driven trucks before the war, so this was a natural fit for him.

There is a famous piece of film footage that shows the North Shore Regiment (New Brunswick) disembarking from their landing craft at 8:10 AM as part of the first wave at Juno.

By lunchtime, that first wave had largely secured the beachhead and had begun their advance inland. Held in reserve was the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade and the Sherbrooke Fusiliers (27th Armoured Regiment) who began their landing around that time. As they came ashore, the beach became crowded and a became a tempting target for indirect German machine gun fire and artillery.

The LCT4 carrying mixed elements of the 27th dropped its front ramp to disgorge its cargo. Tozer’s CMP rolled down the ramp and onto a water-covered sandbar. Advancing towards the beach, the truck plunged off the bar and rapidly filled with water. Under orders not to leave his truck, Lorne would spend some ‘uncomfortable’ hours up to his armpits in water in the cab of his truck under machine and mortar fire. It was mid-afternoon before the Sherbrookes had enough time to use one of it’s M-4 Shermans to affect a rescue. Wet but unwounded, Lorne thus began his adventures in Europe. He spent the first night of that adventure on the road to Caen.

The 27th Armoured Regiment, as the Sherbrookes were officially known, landed over sixty tanks and 800 troops that day. Their role was unique in the Royal Canadian Armoured Corp as they were deployed in an infantry support role and not as an armoured brigade. They suffered their first casualties, twelve logistics trucks, near the town of Iffs on that first day.

Lorne later recalled that his toughest time was at Caen. Initially the city was to be captured on the first day, but the Canadians and British only succeeded in finally driving the Germans out months later in August. Lorne’s job was to carry supplies forward to the fight. He recalled a stretch of four straight sleepless days, loading the truck with fuel, food, ammo and supplies at the beachhead and returning from Caen with the truck full of bodies of Canadians, over and over. It was one of his most vivid and worst memories.

The Sherbrookes were involved in the battles of Carpiquet Airfield, Caen, Falaise Gap, clearing the channel coast ports, the Scheldt, the Liberation of Holland and the crossing of the Rhine. Sadly, they were also be associated with the notorious Ardenne Abbey Massacre. Throughout all of this, logistics trucks worked steadily, carrying supplies. Though he shared very little of it after the war, Lorne saw it all from the cab of his CMP.

There were a few memories he shared. For example, losing his front teeth, crashing a Sherman into a store or how the guys in his unit awarded him a clean-living certificate. One of his favourite stories was about running into another Maritimer in Holland. His unit was laid up for the night when they came under intense artillery fire. As per his orders, he took shelter under his gas truck. A few moments later, another man threw himself in beside him, swearing in Mi’kmaq. Lorne loved to talk, had grown up near the Metepenagiag Nation (formerly Red Bank Reserve) and had worked in logging camps, so he had picked up enough Mi’kmaq to be conversational. Without missing a beat, he turned to the man and said, in the same language, “that was not very polite”. After the other soldier got over his surprise, the two Maritimers conversed in Mi’kmaq about home under heavy artillery fire. He could not remember the man’s name, but apparently, he was from around Bathurst.

Lorne’s unit crossed over the Rhine and into Germany on a pontoon bridge. They were near Düsseldorf, close to the Aachen Airport when the war ended. Lorne did not remember any celebration but remembered feeling relief. He was involved in the turning over of equipment to the newly reconstituted Dutch Army. Very little of Canada’s war fighting material was shipped back to Canada.

Another of his favourite tales occurred after the fighting ended. Lorne signed a jeep out to visit his best friend, who had been assigned to a different unit as a cook, but was not that far away when the fighting ended. On his return trip, he was stopped at a British Checkpoint, and the MPs inspected the jeep’s serial number. He was arrested on the spot. The vehicle had been stolen from a meeting of Commanding Officers in Brussels. Lorne was turned over to his Commanding Officer (CO) for disciplinary action. After a brief discussion, he was docked a day’s pay. It turned out his CO had stolen the jeep to replace his own missing jeep.

Lorne was released from the army in March 1946 after spending a month in a sanatorium to deal with stomach issues. On May 30, 1946, he married Margaret Whitney, whose picture he had carried glued to the back of his mirror throughout his time in Europe. He later worked for the Miramachi Timber Resources mill in their fire and safety section. He and Margaret went on to have three children and raise their family in Whitney, NB. Lorne hated fireworks his rest of life and suffered from ongoing stomach issues. He died at the age of ninety-two of a heart attack. To the end, he was a man who loved nothing more than to sit and have a friendly chat with someone.

Guest written by Kris Tozer for Honouring Bravery

Sources

Royal Canadian Legion: New Brunswick Command. Military Service Recognition Booklet. Moncton, NB, Fenety Marketing, 2011.